There’s a back story – a love story – to the remarkable quartet by Mendelssohn that the Attacca Quartet brings to MT later this month. A love story that lies in the shadow of the powerful, intellectually compelling A minor quartet, Op. 13, the first quartet that Mendelssohn wrote for a public audience.

In it, the 18 year-old composer is prepared to throw caution to the winds in a way he would find impossible for most of his adult composing life. It was something of a gamble – and Mendelssohn’s risk-taking resulted in one of the cornerstones of today’s quartet repertoire.

By bringing together the spontaneity of the moment with deeply considered rational thought, the young Mendelssohn took the string quartet into territory the genre had not previously visited. “The subtlety of the young Mendelssohn’s procedure is intellectually breathtaking,” says the prickly, notoriously demanding critic and pianist Charles Rosen, “but it ends up as deeply expressive.”

The expressiveness, in part, stems from Mendelssohn’s bright idea of basing the quartet on the music of a short love song he had written earlier in 1827. Titled Frage (‘Question’), this slender slip of a song plays by the rules and conventions of polite society, raising the temperature of the blood by a single degree at the most – on a hot day. But it’s in the transformation of art song to string quartet that Mendelssohn’s genius shines through. The song becomes the goal of the entire quartet. “You will hear its notes resound in the first and last movements, and sense its feeling in all four,” Mendelssohn wrote to the Swedish composer Adolf Lindblad. “I think I express the song well, and it sounds to me like music.” Mendelssohn even titled the song “Thema” and published it facing the first page of the quartet when the quartet full score was first published in 1842.

Frage (‘Question’), Op. 9 No. 1

Is it true

That you wait there for me

In the arbour by the vineyard wall?

And ask the moonlight and the stars

About me too?

Is it true? Speak!

What I feel, can only be understood

By she who feels as I do,

and is true to me

Forever, remains forever true

‘Is it true?’ – the first words of the song – open the quartet as a short, questioning motif that will underpin the entire work. They also echo another rising, questioning musical motif ‘Muss es sein’ (‘Must it be?’) from Beethoven’s final string quartet, Op. 135 – by means of which Beethoven constructs an entire movement in search of a resolution. Beethoven had died earlier the year Mendelssohn wrote his A minor quartet. His entire score is riddled with technical ideas borrowed from four of the late Beethoven quartets, recently published – and, of course, the most progressive music of the day. While Mendelssohn quickly absorbed and built upon this music, few at the time understood it. Mendelssohn’s father Abraham disliked late Beethoven and racked his brains trying to figure out what his son was trying to say with his A minor quartet. Then, much to his son’s dismay, he concluded that he hadn’t been saying anything at all.

But back to that song. The 18 year-old Mendelssohn wrote the words himself, disguising his authorship with the pseudonym ‘H. Voss’, (according to the memoirs of his brother-in-law Wilhelm Hensel).

Who was the object of his attention?

By 1827, the year the quartet was written, Betty Pistor had been a childhood friend of Felix and his younger sister Rebecka for several years – from the time that Felix sang alto in the Berlin choir to which they belonged. Musical parties were frequently shared in both musical households. In 1828, Betty Pistor’s astronomer father purchased the musical estate of Bach’s son Carl Philipp Emanuel. With the opportunity of frequent visits to the Pistor family home, Mendelssohn eagerly took on the task of cataloguing and sorting Bach’s papers. In 1827, both young musicians had become members of the select Berlin Singakademie group directed by their mutual teacher Carl Zelter, Mendelssohn’s boy alto voice by now traded for the role of piano accompanist. Mendelssohn was 18, Betty (Dorothea Elisabeth Pistor (1808-87)), one year older.

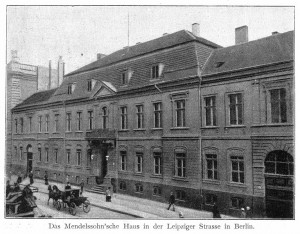

The Mendelssohn family home at 3 Leipzigerstrasse, Berlin became the Upper Chamber of the Prussian Parliament after Mendelssohn's death. Mendelssohn's mother described its garden as "a park, with splendid trees, a field, grass-plots and a delightful summer residence."

“I am composing a quartet for you,” Mendelssohn told Betty the following year. This was to be his next quartet, in E flat (both were published in 1830). But Betty did not know that Mendelssohn added the secret dedication ‘To B.P.’ on the score and frequently referred to it in letters to his sister and friends as the ‘B.P.’ quartet. In the previous summer, while working on the score in England, Mendelssohn wrote to his close friend, the diplomat Karl Klingemann, of “carnations lying near me on the score of the quartet for B.P.” Then, in January 1830, to mark Betty’s 22nd birthday, Mendelssohn gave her a copy of another song he had written and copied onto fine blue manuscript paper, with an original sketch by his brother-in-law on the cover. The young musicians met, as usual, at the Singakademie choir rehearsal. “We were very merry along the way there,” Betty recalled in her family memoirs.

Just three months later, writing to his friend the violinist Ferdinand David, Mendelssohn’s shock is palpable: “Hear now and take alarm: Betty Pistor is engaged. Totally engaged. She is the legal property of Dr. and Professor of Jurisprudence Rudorff. I authorise you to transform the ‘B.P.’ on the score of my quartet in E flat to a ‘B.R.’ as soon as you get confirmation of their marriage from the Berlin newspapers. It will take just a skilful little stroke of the pen – it will be quite easy.”

Betty Pistor did not hear of the dedication until three decades later. According to the Rudorff family memoirs, written by her son, the composer, conductor and teacher Ernst Rudorff: “Betty’s feelings for Felix Mendelssohn were never mixed with any elements of passion. . . She was the elder of the two, and it is known that in early youth, a girl is uninterested in younger men.”

What more could he say? Betty Pistor was, after all, his mother!

Attacca Quartet – Haydn, Prokofiev, Mendelssohn

Thursday September 27, 2012 – 8:00 pm. Jane Mallett Theatre, St. Lawrence Centre for the Arts, 27 Front Street East, Toronto

© copyright Keith Horner 2012