When the Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields Chamber Ensemble brings the Mendelssohn Octet to MusicTORONTO at the end of the month, we’ll be treated to a work that has been at the heart of the ensemble’s repertoire since they were founded almost a half-century ago. It’s music they have played more frequently than any other work . . . . music that R. Larry Todd, today’s leading Mendelssohn scholar, told me in an interview in a Leipzig hotel room a few years ago, “catapulted 16 year-old Felix Mendelssohn into the Western canon of ‘great’ composers.”

As a composer, Mendelssohn peaked earlier than Mozart – possibly, in part, because his father had a thriving private banking business to attend to and saw to it that his four children had an intensive, well-rounded education in the family home from the best instructors. Or, maybe it was just luck of the draw. Mozart’s education, on the other hand, was frequently undertaken on the road, in breaks between concerts, in carriages, in rented accommodation, while travelling throughout the European musical capitals in pursuit of gold snuff boxes.

Mendelssohn wrote the Octet for the 23rd birthday of his violin teacher, Eduard Rietz, for whom he had already written a concerto and sonata. In the Octet, Mendelssohn’s concerto-like writing for the first violin within a chamber-music framework elevates Rietz’s fiddle to first among equals – an appropriate role, perhaps, when teacher and pupil and other musicians gave the première of the piece at one of the family’s Sunday noonhour musicales, a well-attended feature on the Berlin social calendar. The concept of the piece is ground-breaking. Mendelssohn paints in myriad instrumental colours, ranging from the hushed monochrome unison at the end of the Scherzo to the burst of multi-coloured hues in the eight-part fugal exuberance that follows. Though I find that there are still musical discoveries to be made in this innovative, four-movement Octet, the circumstances of its composition have long intrigued me.

Mendelssohn’s family life at the time of composition was not without its adventures, as anyone who has undergone a house move and renovations might agree. On February 18, 1825, Mendelssohn’s father Abraham had purchased a big pile at No. 3 Leipzigerstrasse, Berlin, just around the formerly baroque, still octagonal platz where you can find the present-day Canadian Embassy. The mansion, imposing though run-down, had earlier served as a silk mill and was next door to the royal porcelain factory. Abraham Mendelssohn’s plan was to return the mansion to the grand family home that Heinrich von der Groeben had designed it to be nine decades earlier, around 1835. Abraham and his wife Lea also had plans for a third floor addition drawn up, but they were shelved.

Leipzigerstrasse 3, two storeys and 19 windows wide, into which the Mendelssohn family moved around July 1825. The Prussian state purchased the building from Mendelssohn’s brother Paul in 1856. It became the Upper House (Herrenhaus) of the Prussian Parliament. An unknown photographer took this picture shortly before the building was demolished in 1898.

While work on the house proceeded, the family moved into a summer house in the garden at the rear. This Gartenhaus was at the far end of a substantial, half-acre inner courtyard, with the main house and its two wings, stables and carriage house forming the other three sides. Mendelssohn’s musical education continued through the move from the previous family home at Neue Promenade No. 7. Even the family’s Sunday musicales, begun in 1822, continued in the 16-room, three-kitchen summer house, with its fresco-painted central saal, which, according to his nephew Sebastian Hensel, could hold ‘several hundred.’ That’s quite a ‘summer house,’ even if some of the audience was listening from outside the sliding glass doors which overlooked a park of about seven acres (almost 3 hectares).

It was here, living in the Gartenhaus, with renovation work in full swing, during the summer and Fall months that Mendelssohn wrote his earliest masterpiece, the Octet Op. 20. His ability to focus on a project and to multi-task was exceptional. A friend (Julius Schubring) recalls chatting with him the following year on a variety of unrelated subjects while he was at work composing the Trumpet Overture in C – or ‘copying out’ as the young Mendelssohn put it of an orchestral work which was already fully created and scored in his mind, if not yet on the page. Mendelssohn’s musical education was still in progress, generally together with that of his older sister Fanny, an exceptional musician in her own right, already beginning to act as a trusted go-to editor for Felix as he composed. Schubring’s picture of his friend, (put together after Mendelssohn’s death and after his own collaboration in the preparation of the librettos for both St. Paul and Elijah), next mentions Mendelssohn’s skill as an athlete, regularly doing a vigorous half-hour work-out on the horizontal pole and bars set up in the garden. Mendelssohn also swam well and, like any well-to-do upper class Prussian youth of the time, was a good horseman. He also danced well, winning many friends in his youth, but could not skate. Curiously, though a good chess player, Mendelssohn had a hard time with math.

After visiting Paris before composing the Octet, Mendelssohn’s ‘grand tour’ lasting several years began in 1829 with trips to England, Scotland and Wales.

After visiting Paris before composing the Octet, Mendelssohn’s ‘grand tour’ lasting several years began in 1829 with trips to England, Scotland and Wales.

In an age before photography, the young traveller captured many of the scenes in hastily-made sketches and watercolours.

His skill as an artist resulted in some 300 works.

↑ The sketch of Dunollie castle on the isle of Mull captures something of the mystery and wildness of the Scottish Hebrides. This trip also inspired the earliest musical sketches for the Hebrides overture.

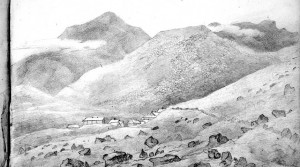

→ To the right, Mendelssohn’s sketch of Ben More, on the Isle of Mull, the highest peak in the Inner Hebrides.

At the end of 1825, Mendelssohn moved from the summer house at Leipzigerstrasse 3 into a room on a mezzanine level in the left-hand wing of the main house. But he was to return to the Gartenhaus with what his nephew Sebastian Hensel referred to as its ‘deep loneliness of a forest,’ steps away from the bustling city of Berlin, the following summer. Then, in the space of just a month, July 7, 1826 to August 6, his imagination — plus a good deal of reworking under the supervision of his composition teacher Adolph Marx — conceived another perfectly shaped composition. The Overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream follows the lead of the Octet in exploring the boundaries between absolute and program music. Mendelssohn never again brought the same spontaneity, certainty of touch and vividness of imagination to a composition as he did in his teens in the Octet and music to A Midsummer Night’s Dream, free to explore his private world in the seclusion of the Gartenhaus . . . in the former hunting grounds of Frederick the Great which now form the site of present-day German Bundesrat, or Federal Council.

Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields Chamber Ensemble – Raff, Shostakovich, Mendelssohn

Thursday October 31, 2013 – 8:00 pm. Jane Mallett Theatre, St. Lawrence Centre for the Arts, 27 Front Street East, Toronto

© copyright 2013 Keith Horner