For decades I’d read about an abandoned 13th. century Carthusian monastery to which Fryderyk Chopin and his lover George Sand retreated, far away from the prying eyes of Parisian society. The atmosphere it evokes, both from Sand’s pen and from a number of biographers, sounded so quintessentially romantic.

Legend has it that while staying in one of its monk’s cells, Chopin heard the unceasing dripping of rain water throughout the day and night while completing his collection of Preludes. This inspired the so-called Raindrop Prelude, Op. 28 No. 15, the longest piece in the collection and an anchor and focal point, with its evocative, timeless, nocturnal dreaming.

Now here in front of me, exactly 180 years later, early one December morning, is that monastery and former royal residence, looming large and rather forbidding, with its austere facade. What, I wondered, lies beyond those walls?

Our journey has taken us from Barcelona on the Spanish mainland to the island of Mallorca (Majorca) – certainly with more comfort than that of Chopin, Sand, her two children Maurice (then 15) and Solange (10), plus a maid, Amelia.

They sailed from Barcelona on the El Mallorquin, a steamer primarily designed to transport a cargo of 200 black Mallorcan pigs every week to the markets of Barcelona.

That dubious pleasure lay ahead for the party on what would become a hastily arranged retreat from the keenly anticipated comforts of the Mediterranean island.

On arriving on the island, in Palma November 8, 1838 at 11:30am, there were no inns to be found (none on the island at all, if Sand’s colourful, though malicious travel memoir Winter in Mallorca (1842) can be believed – which it can’t!).

Chopin’s initial reaction to the island was also favourable.

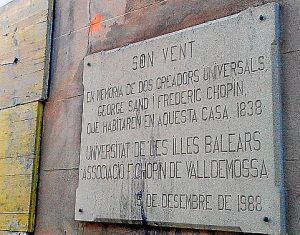

On November 15, he wrote from Son Vent to fellow pianist Julian (Jules) Fontana in Paris.

“Here I am in the midst of palms and cedars and cacti and olives and lemons and aloes and figs and pomegranates,” he enthused.

“The sky is turquoise blue, the sea is azure, the mountains are emerald green … all day long the sun shines and it is warm, and everybody wears summer clothes.”

This was too good to be true.

The idyllic weather soon broke, Sand

recounts, and the rains started.

“The damp settled like a cloak of ice over our shoulders and reduced me to paralysis.”

On December 3rd, 1838, Chopin again wrote to Fontana:

“I have not been able to send you the manuscripts (His 24 Preludes) since they are not ready. For the past three weeks I have been as sick as a dog, despite a heat of 18 degrees, despite the roses, orange trees, palms, and flowering fig-trees. I caught a bad cold.

“The first said that I would die.

“The third that I was already dead.”

Chopin’s consumption (tuberculosis) was already being whispered about among the fearful Mallorcans. It was viewed as contagious, much like a coronovirus.

The lease on the villa was quickly broken and the property vacated by the end of the month. Sand was billed extra for a deep cleaning.

Chopin consulted his doctors while the Chopin-Sand party stayed with the French Consul in Palma.

Valldemossa today, with monastery in distance in centre, December 21, 2018, CLICK ANY IMAGE TO ENLARGE

In 1838, however, George Sand recalls a very different experience, travelling in a cartana – a kind of springless post-chaise pulled by a horse or mule:

“Ravines, torrents, swamps, quickset hedges, ditches, all bar the path in vain. One does not stop for such trifles, because, of course they are part of the road.

“And yet you often reach your destination safe and sound, thanks to the steadiness of the carriage and the strength of the horse’s legs, though one wheel may run on a mountain and the other in a ravine . . .”

Now, it would seem, in this mountain-top village in the Tramuntana range, Chopin the composer and Sand the writer would have the solitude and peace they were seeking, both for work and for health.

But what attracted the Polish composer-pianist and French novelist, memoirist and social activist to one another in the first place?

Born Amandine Aurore Lucille Dupin in 1804 (six years before Chopin), Sand acquired her pen name via one of many lovers, Jules Sandeau, with whom she co-authored her earliest publications.

“I dashed back and forth across Paris and felt I was going around the world . . . Nobody heeded me. Or suspected my disguise . . .”

Victor Hugo concluded: “George Sand cannot determine whether she is male or female . . . but it is not my place to decide whether she is my sister or my brother.”

Chopin, on the other hand, recoiled from public life.

He preferred the salon to the concert hall and composition to the gladiatorial competitiveness among the lions of the keyboard he encountered in Paris.

Fellow pianist-composer Ignaz Moscheles observed in 1839: “His appearance is exactly like his music; both are tender and schwärmerisch” (fanciful, dreamy, enthusiastic).

“Chopin was feminine in looks, gestures, and taste,” according to his pupil Adolf Gutmann.

Opposites attract and never more so than with Chopin and Sand.

They were opposites in politics, he a traditionalist, favouring the company of the aristocracy, she a full-throated child of the French Revolution, egalitarian in her views, provocatively unorthodox in her attitudes.

His ancestry was middle-class and devoutly Catholic; hers aristocratic, advantaged and liberal-minded.

Chopin was reserved in his thoughts, refined, even aloof. Sand, meanwhile, lived life like a book – and, frequently, included life’s characters, thinly disguised, in her own writings.

Today, she would have posted prolifically on social media; in 1838, her followers had to buy her books!

“Together they were to become one of the oddest couples in Europe,” says Chopin biographer Jeremy Siepmann.

The monastery’s charter-house corridors, deconsecrated in 1835, still maintain a stark simplicity today

“This is the devil’s own country as far as mail, the population and comforts are concerned,” Chopin writes days after arriving in Valldemossa.

“The sky is as lovely as your soul; the earth is as black as my heart.”

“This Charter-house has no architectural beauties, but is a series of sturdy, amply-designed buildings,” Sand writes in A Winter in Mallorca.

“Its massive walls of dressed stone enclose an area which would have sufficed to house an army corps.

Yet the whole edifice had been built for only 12 monks and their prior.

The ‘new cloisters’ alone – at various periods, three Carthusian monasteries have here been built on to one another – give access to 12 cells, each consisting of three spacious rooms.

At right angles to these cloisters run two lines of chapels, 12 in all; because each monk had his own chapel, where he used to retire for solitary devotion.”

For three generations, the Ferrá-Capllonch family claimed No. 2 as the only authentic Chopin museum in Mallorca.

A court case in 2004 – with Chopin’s piano as evidence – put an end to the feud, which endured over three generations.

In other words, for three generations, visitors to Valldemossa were tricked into paying an admission fee to be misled into believing they were in the Chopin-Sand cell. The piano they saw there was proven to have been built a decade after Chopin’s visit.

References to this museum are still, confusingly, all over the web.

Its arrival was delayed and then the high import duties required much negotation.

The piano remained in Mallorca because high export duties would have been demanded and – more importantly – Chopin’s consumption made it an object which no-one wished to handle.

The ever-resourceful author persuaded the French Consul’s chef to send provisions from Palma.

She even purchased a goat and a sheep for milk.

“Since it rained off and on for two months [December and January are the rainy season in the Balearic Islands] we frequently nibbled bread as hard as ship’s biscuit and dined like true Carthusians,” Sand wrote.

In an act of revenge, she even referred to Mallorcans as “barbarians, thieves, monkeys and Polynesian savages” in A Winter in Mallorca.

The caption, in French, reads: “Visit of the priest who explains to us what snow is (as if we didn’t already know).

“Sand was a beautiful woman, endowed with a face full of intelligence, animated by her beautiful black eyes . . .”

“Chopin was very ill. He came looking for southern weather to restore his health . . .”

CLICK THE IMAGE FOR MORE

The compact, three-room museum contains original lithographs by Chopin and Sand, letters and manuscripts (or facsimiles) related to Mallorca, medallions, sculptures and other memorabilia.

Chopin, with his small, fine-boned hand, was heard to advantage in the salon, rather than the larger concert hall. His touch was sensitive and nuanced, never forceful.

Chopin was an innovator, integrating carefully shaded dynamics, subtle use of the pedals, fresh developments in keyboard fingering and refined use of rubato that all blossomed when heard in the intimate salon.

My hand (on top of a display case (about 18 inches above the exhibits) is substantially larger than the cast made of Chopin’s left hand by Auguste Clésinger, French sculptor, painter and husband of Sand’s daughter Solange [but the tale of this marriage is a sorry tale for another day . . .]

Even in late December, the view from Cell #4 balcony is stunning.

“It is a sublime picture: the foreground framed by dark, fir-covered rocks, the middle distance by bold mountains fringed with stately trees,

the near background by rounded hillocks which the setting sun gilds warmly, and on whose crests the eye can make out, though a league away, the outlines of microscopic trees, delicate as a butterfly antennae, but as sharply black as the stroke of a pen in Indian ink on a field of sparkling gold.

Yet the sea lies still farther in the background and, when the sun returns in the morning and the plain resembles a blue lake, the Mediterranean sets a limit to this dazzling vista with a strip of brilliant silver.”

– from A Winter in Mallorca

Sand, by now, was performing heroic service to her family. She was providing the necessities of life, overseeing her maid and a hired local cook. She was teaching her children during the day, nursing the declining Chopin, and still finding energy to write by night, revising her provocative 1833 novel Lélia and completing Spiridion, a gothic novel, examining and critiquing monastic life.

Chopin then began coughing blood.

Sand made all the travel arrangements, with many odds stacked against her.

“And the reason for this unfriendliness?” Sand wrote to her friends. “It was because Chopin coughs, and whosoever coughs in Spain is declared consumptive; and he who is consumptive is held to be a plague-carrier, a leper. They haven’t sticks, stones and police enough to drive him out, for, according to their ideas, consumption is catching and the sufferer should therefore be slaughtered if possible, just as the insane were strangled two hundred years ago. We were treated like outcasts in Mallorca – because of Chopin’s cough and also because we didn’t go to church.”

They set sail for Barcelona February 14, 1839, together with 200 pigs, Chopin coughing and haemorrhaging badly.

They arrived in Mallorca as lovers; they left with a different relationship.

“I care for him like a child and he loves me like a mother,” Sand confided to Charlotte Marliani.

Chopin was nursed back to health in Barcelona, then Marseilles and, finally, at Sand’s chateau at Nohant in France.

Life in Nohant and Paris resumed, with Sand continuing to provide the secure environment Chopin needed to compose.

During their long and complex ten-year relationship, Chopin composed some of his finest works – the 24 Preludes, the B-flat and B minor Sonatas, the C-sharp minor Scherzo, F minor Ballade, the Polonaise-fantasie, and many waltzes, mazurkas, Polonaises,nocturnes and other works.

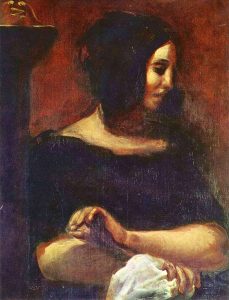

George Sand, Fryderyk Chopin, portrait after Delacroix, 1838/2008, currently in the Louvre museum.

The two lovers posed for their friend Eugène Delacroix before leaving for Mallorca. The painting was considered unfinished and remained in the artist’s possession until his death.

It was then sold several times and eventually cut into two parts,with some features removed.

The George Sand part is at the Ordrupgaard museum in Copenhagen, the Chopin part now at the Louvre.

This is a 2008 hypothetical reconstruction of the painting, based on Delacroix’s sketch and completed sections.

Stephen Hough plays music by Chopin in his January 19, 2021 concert for MusicTORONTO.

Janina Fialkowska has another Chopin set, April 27, 2021.

Blog post copyright © 2020 Keith Horner

Its hard to find knowledgeable people on this topic however you sound like you know what youre talking about! Thanks .

A more truthful writing and rare observations

in a historical setting..two human beings

tried to enjoy…thank you..so very much