The eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month – one hundred years ago today – was only the beginning of the war effort for English composer Gustav Holst.

The eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month – one hundred years ago today – was only the beginning of the war effort for English composer Gustav Holst.

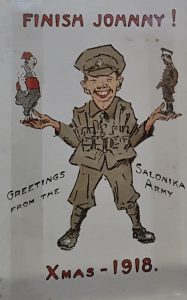

Having sailed from Southampton October 29, 1918, Holst was less than half way into a month-long journey across worn-torn Europe on his way to Salonika, Greece when the Armistice was declared.

Holst did not end his arduous travels at 11:00 am on November 11, 1918. Neither did World War 1 end an hour before noon.

Treaties had to be negotiated and signed. Empires had to be further broken up. Populations redistributed.

The Allied Forces in Salonika, were to be kept on the Eastern Front (Southern Aegean / Sea of Marmara region) almost five more years, until August 1923. Holst was with them in Salonika (present-day Thessaloniki) and Constantinople (present-day Istanbul) part of this time, on active service with the British Expeditionary Force with the YMCA for some eight months.

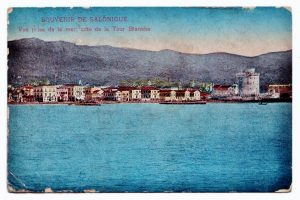

Salonika postcard mailed in 1918. The photograph was taken earlier since the defensive chemise around the White Tower was demolished in 1917. A massive fire also devastated much of the Old Town in 1917. The White Tower, now a museum, remains an iconic symbol of present-day Thessaloniki

His mission with the YMCA Auxiliary?

As Music Organiser, to bring music to help heal and revitalise exhausted Allied troops waiting to be demobilised, by one-on-one teaching, organising choirs, an orchestra, concerts and lectures. But even before he set sail for the Eastern front, there was much to be done.

YMCA Music Section logo

Holst’s brother Emil, working since 1908 as a Broadway actor under the name Ernest Cossart, later a successful movie actor, was badly wounded while serving in the Canadian army during WW1

At the beginning of the war, Holst and his friend Vaughan Williams, both around 40 years old, had volunteered for military service. “The recruiting office had little use for a man who could hardly hold a fountain pen, let alone a rifle, and who was unable to recognise his own family at a distance of more than six yards,” his daughter Imogen wrote in her biography of her father.

Holst later heard about Vaughan Williams’ work with the Royal Army Medical Corps in Salonika and France. “Having been trained as a 6” Howitzer man, I’ve been bunged into a 60 pounder!” RVW wrote to his friend at one point.

As the war went on, his fellow composers and friends George Butterworth, Cecil Coles, and Ernest Farrar were all killed in action.

His wife Isobel was a volunteer ambulance driver throughout the war.

During the repeated air raids over London, Holst applied for work that would help the war effort, only to face rejection.

Meanwhile, with his thoughts constantly on the war, Holst continued teaching at St. Paul’s Girls’ School and, in the evenings, teaching adult classes at Morley College. More significantly for us, he kept busy composing in the soundproofed studio the school had constructed for him.

He wrote the ground-breaking Suite The Planets between 1914 and 1917, having to dictate part of the movement he completed last, Mercury, the Winged Messenger, because of the neuritis in his right arm.

Although he always downplayed its direct connection with WW1, the mighty Mars, the Bringer of War, completed just months before the outbreak of war in August 1914, clearly anticipates the horrors to come.

Holst’s name presented problems. Born Gustavus Theodore von Holst to musical parents, his German ancestry dated back to his great-grandfather Matthias (1769–1854) born in Rīga, of German stock – he was a composer, pianist and teacher to the Imperial Russian court in St Petersburg. This would have been a bit of a mouthful to explain to war-weary troops in Salonika.

Anti-German sentiment even against a British musician born in the comfort of a middle-class Cheltenham home was not in short supply in 1918.

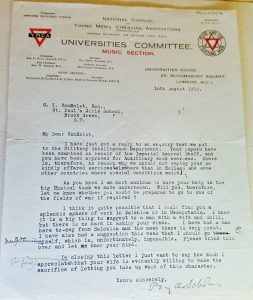

G. T. VonHolst Esq’s application for Auxiliary work is accepted by the government’s Military

Intelligence Department

CLICK ANY IMAGE TO ENLARGE

Holst changed his name by deed poll September 24, 1918.

Centre-right, Holst’s birthplace in 1874, then 4 Pittville Terrace, now 4 Clarence Road, and the Holst Birthplace Museum since 1975

(He was, of course, beaten to it by Mr and Mrs Saxe Coburg-Gotha, henceforth to be known as George and Mary Windsor).

Military training followed, in Nottinghamshire. “I’m going with the YMCA to Salonica for a year – it is a special educational mission. In order to be of more use I am dropping the ‘von’. I’m here under canvas and in mud learning my job.” he wrote to a friend at the time. Then Holst sought out some advice in piano tuning and maintenance, equipping him with some of the skills he would need in Salonika.

A welcome parting gift came from a friend, Henry Balfour Gardiner (great-uncle of the conductor Sir John Eliot Gardiner). He hired Queen’s Hall and the London Symphony Orchestra for the morning of September 29, 1918 for a private read-through of The Planets with a small invited audience. There was time for a quick rehearsal with Adrian Boult leading the musicians and a chorus made up of

A report from London’s Musical Standard outlining the work of the YMCA in camps throughout the field of war, at troop hospitals at home and in internment camps in Europe.

Holst’s posting is mentioned.

CLICK TO ENLARGE

members of Holst’s evening educational classes at Morley College and a few girls from St Paul’s. The public premiere of the suite had to wait until November 15, 1920.

Holst finally arrived in Salonika December 1, 1918 and quickly settled into a shared room at the YMCA Education Office, 19 Evonon.

Two days later,, an entry in his diary reads: “Wrote lecture in morning, singing lesson Lucas Collins, Theory Lucas Collins, Interview Hagget, and see Bates at night at H2.” (the main YMCA hut in the city).

Still, music education must have been an uphill struggle for all concerned, though Holst appears to have done his best to create a welcoming environment out of his music room. Before the end of the month he wrote to his wife:

“It has a bed, two chairs, three tables and many shelves made of packing cases. I have been there every afternoon except one when I went to the Scottish Women’s Hospital to arrange teaching wounded French and Serbians (I fancy teaching tonic solfa to Serbians!) and men come in for lessons whenever they can. It is a free and easy

arrangement that appeals to them greatly.”

For three long years, the Allied expeditionary force, based in Salonika in the North of a divided Greece, had fought to support Serbia in defending a 250-mile front against Bulgarian and pro-German forces.

By late September 1918, suffering thousands of deaths on both sides, widespread influenza, rampant malaria (with over 160,000 cases in the British Salonika force alone) and exhaustion after the extended stalemate in primitive living conditions, the Allied contingent entered Bulgarian territory.

The Salonika Armistice came into effect September 29, 1918, the very same day that Holst’s The Planets introduced both war (Mars) and peace (Venus) to a London concert hall.

Another armistice was declared when the Ottoman Empire collapsed a month later. Holst would later travel with the Salonika Forces to Constantinople.

Holst had a keen eye when walking around the battered city of Salonika.

On Christmas Day, 1918 he wrote to his wife:

“I went on a long walk and visited an old church that was first a church and then a mosque and then a church again and now a ruin because it was burnt by the terrible fire last year and since then has been used as a living place for starving refugees.”

“Our Camp Concert” is the title of this postcard below, produced by the YMCA c1916. Even though it may have sent the men running, music was an important part of camp life.

On other occasions, Holst traveled to many of the other camps in the region, giving lectures, lessons and training choirs.

January 25, 1919 finds him in Serres and his diary reads:

“Walk alone on hills till 1 am. Motor across Struma plain – see men ploughing. Arrive Serres midday . . . Lecture 7 to 8:30. Sleep on ground. Quite warm. Heard wolves in distance.”

One month later, Holst organised a “Concert of Music of British Composers” in the large canvas theatre of the 52nd General Hospital.

One of the Pomp and Circumstance marches of Elgar (little doubt that it was Land of Hope and Glory) opened the ambitious event. A part-song for female voices by Elgar was also included.

Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast, by Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, the most popular oratorio among British choral societies since Handel’s Messiah, was the centrepiece. And there was music by Purcell too, though nothing by Holst himself.

“Hundreds, including a number of red-hatted staff officers, were turned away. Some 500 sat on chairs, others on the ground, in the orchestra, in the dressing-rooms, behind the chorus and in other odd corners (five men and a dog sat on the double-bass case!).” (The Musical Standard)

By March, Holst and most of the entire camp were re-posted to Constantinople, present-day Istanbul. Buoyed by the success of the Salonika concert, Holst repeated the event at the Theatre Petits-champs in Constantinople, this time over six consecutive evenings in June.

Holst felt that the results were mixed. But his followers had enduring memories long after being demobbed and resuming lives cruelly interrupted by the war.

Laura Kinnear, curator of an intimate, well-documented exhibition at the Holst Birthplace Museum in Cheltenham titled Gustav Holst’s WW1 with the Salonika Forces – to whom I am indebted for much of the information and graphics for this blog post – quotes one soldier who wrote to the BBC in September 1950:

“My happiest memory was of the morning visits with a few of his keener followers to where, seated at the organ with the men clustered around, he used to teach us simple harmonies . . . The greatness of Holst as a man was enhanced by his innate humility and his desire to enrich the musical understanding of a crowd of very ordinary soldiers. This episode will remain with me as one of the most fragrant memories of my life.”

Holst left for England towards the end of June 1919. He had not found time or the inspiration to compose while in Salonika or Constantinople and his wartime years of composition had produced little that directly reflected its impact. But there was more to come and it was to result directly from his first-hand experience among the troops on the Eastern Front.

The Ode to Death, for chorus and orchestra,was written that summer upon his return. It is the most powerful and, perhaps, meaningful of his choral works, written in memory of lost friends. The words are by Walt Whitman taken from When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d, the American poet’s elegy upon the assassination of Lincoln. Holst turns this short choral work into a music of transcendent beauty, conveying not a sense of despair of the millions of lives so futilely lost, but rather a feeling of pride in their sacrifice and profound gratitude for what they achieved.

© copyright 2018 Keith Horner – [email protected]