Esterházy Palace overlooking the town of Eisenstadt in present-day Austria

It is still quite easy to imagine walking in the footsteps of Joseph Haydn in Eisenstadt, a small town in the Austrian Burgenland, less than 50 km south-east of Vienna. Eisenstadt was the principal residence of the Esterházy family, whom Haydn served for more than four decades, and it was here that he created much of a vast catalogue of musical compositions.

Haydn received winter and summer livery each year as part of his Esterházy salary

Walking a few steps beyond the palace, to the left of my photo above, you can find the Margaretinum. It’s now a parish centre and, before that, a convent. Even earlier, the building housed an apartment where the young Haydn lived with his wife in the early 1760s, when he was appointed Vice-Kapellmeister to Prince Paul Anton Esterházy.

Next door lies the Bergkirche where Haydn played the organ. His remains have lain in its crypt for almost two centuries. Sad to recount, Haydn’s corpse has only been reunited with its skull for a little over a quarter of this time . . . . . . maybe more of this gruesome tale in a later post.

A few minutes walk in the opposite direction, behind the buildings to the right above, there’s the Joseph Haydngasse – which was known as the Klostergasse in Haydn’s day.

No. 21 is the house that Haydn bought in 1766 once he was feeling confident in his future, having taken over the full Kapellmeistership of the Esterházy court.

Joseph Haydngasse, with No. 21 to the centre right

Haydn and his wife lived upstairs, with his copyist Johann Elssler and pupils occupying a former stable on the ground floor.

The Haydn-Haus has been a museum since 1935. Its scope increased significantly after 1998 when the neighbouring property was acquired and carefully restored to allow for more display space.

Its eight rooms aim to give a picture of Haydn and his times in a chronological sequence.

There’s a fine looking Anton Walter piano from 1780, believed to have been used by Haydn. Sadly, I couldn’t find a way of laying a finger upon it.

The Haydn-Haus (centre left) from the opposite direction, looking at the Franziscanerkirche

Anton Grassi bust of Haydn (1802)

A standout, for me, is a craquelé porcelain bust made by Anton Grassi, for which Haydn sat in 1799 and again in 1802. This comes closest to the mental picture of the composer that I have built up for myself over the years through reading about the man and listening to the music.

Autograph scores, original letters and early printed scores which were formerly in the museum now appear to have been moved.

An exhibition Haydn and the Women: 12 stories about music and love coyly delves into Haydn’s sex life, without saying anything that’s new.

Maria Anna Theresia Haydn (bap.1729-1800)

Haydn married Maria Anna Theresia Keller, daughter of a wigmaker, in 1760 having first fallen in love with her sister, destined for a nunnery.

Unlike Mozart, who similarly first fell for the wrong sister a generation later, Haydn did not have a happy marriage.

Both Haydns had affairs and there were no children.

The Haydns were to remain together until Maria Anna’s death in 1800.

Her affair was with the court painter Ludwig Guttenbrunn.

His was (mainly) with the soprano Luigia Polzelli, hired with her violinist husband for the Esterháza opera in 1779, fired by Prince Nicolaus in 1780, but almost immediately reinstated (for the remaining decade of the relationship) at Haydn’s request.

Haydn wrote just one role for Luigia’s limited talents. He did, however, spend much time adapting, rewriting and arranging arias in operas by other composers that were presented in the busy Esterháza season, to best display her way with music described as “light, ironic and charming.”

Haydn is believed to have been the father of her son Antonio. He provided for the young violinist in his will and Antonio’s daughter, in turn, maintained that she was Haydn’s grand daughter.

City plaque showing key Haydn sites in Eisenstadt

Along with the house at Klostergasse 21, the Haydns acquired several plots of land, including a “kitchen garden behind the hospital,” beyond the city walls.

Needless to say “Secrets from Mrs. Haydn’s Garden” is now a tourist attraction in itself, by ticket only.

An inventory drawn up following one of the two fires that damaged the Haydn-Haus during the 12 years that Haydn lived there reveals that he raised pigs and chickens received as part of his salary in this Kräutergarten.

Who knew?

Reluctant to let the Mozartkugel have the market to itself, Eisenstadt’s Altdorfer bakery, dating back to Haydn’s time, recently introduced the delicious Haydnrolle

Haydnsaal and stage in the Esterházy Palace

Haydnsaal rear, balcony and elegant Garden Room beyond

Pride of place in the big house on the hill goes to the Haydnsaal, a 650-seat concert hall with outstanding acoustical and visual elements.

The room dates back to a Baroque building phase when 13th century fortress was transformed into 17th century palace. Attractive ceiling frescos by Carpoforo Tencala tell the story of Psyche and Amor.

Berlin-based manager Andreas Richter programs the April through October concert season on behalf of the Esterházy Foundation. The Banff prizewinning Rolston Quartet will make its debut in the Haydnsaal June 6, 2017 and return the following year.

Richter outlined this year’s annual festival for me in a recent interview.

It runs September 6 – 16, 2017, titled Herbst Gold / Autumn Gold.

More details of the season, including stylish picnic concerts in the

splendid palace grounds HERE.

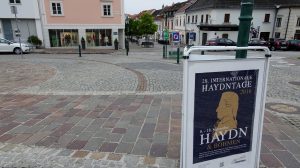

Eisenstadt during a recent off-season visit

Some recent vintages produced on the extensive Esterházy estates.

Details HERE.

Haydn had a comfortable wine allowance of 504 litres per annum!

Haydn led a comfortable, if demanding, life working for the Esterházy family.

Under Prince Nicolaus he and the musicians initially moved between Eisenstadt and Vienna.

By the 1770s, as opera became the centre of the prince’s attention, a hunting lodge at Süttör was transformed into a new summer palace, complete with two theatres, one for opera, the other for marionette opera.

Now, Haydn’s life involved long summer residences at the newly named Esterháza palace, just across today’s Hungarian border.

The scale of the enterprise was huge, peaking in the year 1786, with 125 performances of 17 different operas, all of them under the direction of Haydn, several of them also composed by him.

With less time to spend in Eisenstadt, Haydn sold his house there in 1778 and lived in the accomodation built for the court musicians in the three hubs of their activity: Esterháza, Eisenstadt and, in December and January, Vienna.

With the death on Prince Nicolaus in 1790, opera for Haydn and the Esterházy family came to a crashing halt.

Prince Anton dismissed all the court musicians save his music director Haydn and concertmaster Tomasini.

The classical facade of the Esterházy palace is one of the main legacies of the belt-tightening four-year rule of Prince Anton Esterházy

Haydn, however, survived the downsizing quite well.

He now had a pension of 1,000 gulden per annum from Prince Nicolaus’s will, plus a salary from Prince Anton of another 400 gulden.

With little music at court, the way was clear for Haydn – now the most celebrated living composer in Europe – to accept an invitation to travel to London for two visits in the early 1790s.

His successor, Nicolaus II extended the classical design to the garden facade of the palace. He completed only the centre columns and extensive landscaped gardens in the English style, complete with copses, grottoes, pools and temples, plus glasshouses and even an English steam engine to pump water around the park

His house in Eisenstadt had brought in 2,000 gulden; but his time in London netted a princely 15,000 gulden.

“Such a thing is possible only in England,” the gleeful composer reported after one of his highly successful benefit concerts.

The rich proceeds of Haydn’s travel, together with his astute business sense selling his manuscripts to publishers across Europe, helped him prepare for old age in Vienna.

He purchased a house in 1793 for 1,370 gulden and had renovations done while he was away in the British capital.

With a salary increase to 700 gulden under Anton’s successor, Nicolaus II, and a wine allowance now at 515 litres a year, a complimentary uniform and various lump sum payments, Haydn additionally negotiated apothecary bills into his contract.

These were substantial and were to amount to 1,000 gulden in the final year of his life.

St Martin’s, Eisenstadt’s present-day cathedral. Haydn directed the first performance of his Missa in angustiis, the ‘Nelson’ Mass, from the organ here in 1798

Nicolaus II spent the main season, the winter season, in Vienna, with the main musical performances of a much reduced ensemble (now a wind harmonie of eight and string ensemble of a similar size) taking place in September and October. Haydn’s late masses date from this period.

Haydn’s Bergkirche undergoing restoration,sporting the banner ‘Restoration 2020: we’re saving the Haydn church.’ Haydn’s Bergkirche was originally intended as the presbytery to a much larger church, planned but never built. Throughout the 20th century – except for the year 1945 – to the present day, Haydn’s Seven Last Words has been performed here every Good Friday

Most of these six masses were privately performed on the nameday of the prince’s wife, Princess Marie, during a church service in the Bergkirche.

Incomplete rear of Bergkirche

In Vienna, meanwhile, Haydn was having some of the greatest successes of his life with his two newly written oratorios, The Creation and The Seasons.

By 1806, Haydn was confined to his house and never returned to Eisenstadt.

He was a celebrated figure throughout the musical world, but frail and no longer composing. He was taken to a special performance of The Creation by Princess Esterházy and family, but it proved too overwhelming for him. He had to leave at the end of Part One.

Haydn died peacefully in his sleep at 12:40am, May 31, 1809.

The very beautiful and moving Haydn mausoleum in the Bergkirche

The St. Lawrence Quartet will play two of Haydn’s Op. 20 string quartets, written in Eisenstadt in 1772 and first performed there, for MusicTORONTO, January 26, 2017.

Blog post and photographs © copyright 2017 Keith Horner – [email protected]