“The right type of peasant music is most varied and perfect in its forms. Its expressive power is amazing, and at the same time it is void of all sentimentality and superfluous ornaments. It is simple, sometimes primitive . . . and a composer in search of new ways cannot be led by a better master.”

Bartók had been led by his own advice for more than two decades when he penned these thoughts in an essay in 1930. Folk music is the very life blood of Bartók’s six string quartets, as we’ll hear when the Tokyo String Quartet embarks on a journey through this landmark of the quartet repertoire in their MusicTORONTO concerts this season and next.

The ‘right type’ of folk music implies that, for the Hungarian composer, there must have also been a ‘wrong’ type. This would have been the showy gypsy music that stirred Liszt to write his Hungarian Rhapsodies and Brahms his Hungarian Dances. The ‘wrong’ type also included songs that resembled simple folk songs but which were, in fact, made up by popular 19th century composers.

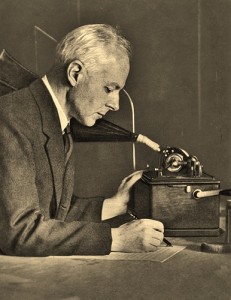

Bartók went in search of the real deal. The older generation of rural villagers, he found, generally held the key to the purest folk song; young people tended to prefer popular song. His colleague and fellow collector Zoltán Kodály was a frequent traveling companion, both of them carrying heavy phonographs initially borrowed from the Budapest Ethnographical Society. “We went into the country and obtained first-hand knowledge of a music that opened up new ways to us,” Bartók said. “Of course, there were occasions when we were received with suspicion,” Kodály admitted. “It wasn’t so bad as long as went on foot, but when we needed a carriage to take all our equipment they smelt a rat, suspecting some kind of ‘business’.”

Recording women could present a problem, Kodály reported. While the men would be glad to cooperate after a glass or two, the male villagers believed that their women-folk only sang when drunk. But by making a social event out of the recording – sometimes playing back recordings to encourage a sense of occasion and greater participation from the villagers – Bartók found that a line-up soon formed next to his phonograph, sometimes even proudly dressed in national costume.

Collecting Slovak folk songs in 1907. Bartók (centre) coaxing a female singer in village of Zobordarazs, now Drazovce, Slovakia

Bartók’s earliest folk song gathering was done with noble, if, ultimately, restricting intentions: “I shall collect the most beautiful Hungarian folk songs and raise them to the level of art songs by providing them with the best possible piano accompaniments,” he told his sister in 1904. Many of his folk songs did, indeed, end up as solo songs with piano accompaniment or as choruses. They also provided the starting point for one of his most straight-ahead and popular compositions – the Six Romanian Folk Dances of 1915. Take a listen to this imaginative concert recording from Budapest which reunites these by-now well-known melodies with their folk origins.

Still, folk song arranging was only the beginning for Bartók. His goal lay both musically and geographically farther afield. He traveled through Transylvania, Romania and Bulgaria between 1907 and 1912. As the First World War approached, he was in North Africa meeting and recording the Berbers.

After gathering an incredible 10,000 recordings, then meticulously transcribing and cataloguing them, Bartók was to write: “The composer does not make use of a real peasant melody, but invents his own imitation of such melodies.” Folk song, in other words, was so much under his skin that it now became his musical language. And this brings us back to the string quartets and two brief glimpses of how Bartók’s scholarly field work influenced his composition.

Folk music, specifically certain types of Hungarian folk music with its distinctive accent on the first beat, colours the cello theme at the beginning of the slow movement of Bartók’s Fourth Quartet. [Click on arrow above for audio – no video].

Its rhapsodic, wonderfully evocative cello theme unfolds against static chords.

Its accents also mirror those of Hungarian speech.

There are many examples of this sort of distinctive melodic writing drawn from folk song and speech rhythm throughout Bartók’s music.

If you continue listening, the cello rhapsody gradually reveals another profound influence on Bartók’s music, the sounds of nature – insects, birds, animals – and the sounds of the night.

one-two

one-two-three.

Tokyo Quartet – Haydn, Bartók Quartets 1 and 2. Thursday March 15, 2012 – 8:00 pm. Jane Mallett Theatre, St. Lawrence Centre for the Arts, 27 Front Street East, Toronto

Posted by Keith Horner