The late 19th century Austrian composer Hugo Wolf was born into a great musical tradition. By temperament, though, he remained an outsider. Song – German art song – was the weapon of choice with which he confronted the Viennese Establishment. With it, Wolf brought the tradition of Schubert and Schumann to a level of intensity and heightened sensitivity to the text that relatively few could fully appreciate. Wolf did little to woo his audience. Irascible, impulsive, yet sensitive to a fault, with mood swings that bordered on the manic-depressive, the humbly-born composer from the provinces (Windischgraz, Styria, now Slovenia) did not hide his ambitions when he arrived as a student in Vienna. His audience was the epicure, not the amateur, he declared. Seven years later, with one volume of song settings of the German romantic poet Eichendorff published, Wolf remained penniless. A failed attempt at a conducting position in Salzburg was the closest Wolf came to holding down what his father viewed as a real job. Exasperated, Philipp Wolf decided that his son was “more out of tune than our piano.”

Wolf’s musical voice – ‘Wölferl’s own howl’ he called it – took a decade to come into focus. Depression and dry periods followed inspired weeks when Wolf was intensely absorbed with composition. With the Mörike songs of 1888, one streaming from his pen after another, Wolf had a breakthrough year that can be likened to that of Schubert in 1814-15 and Schumann in 1840. At a material level, by combining music teaching and accompanying with a knack for attracting benefactors and sponsors among Vienna’s educated elite (not to mention a lifelong mistress from the wife of one of them), Wolf gradually built a reputation with his short, highly polished lieder. “What I now write, dear friend,” he wrote to his brother-in-law, “I write for posterity too. They are masterpieces.”

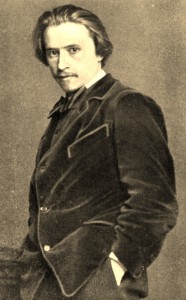

Diminutive in stature, standing a small volume of songs over five feet (154 cm), the 30 year-old Wolf became a cult figure to the next generation of music students. “Hugo Wolf belonged to us and we belonged to him,” the critic and composer Max Graf wrote in his memoirs. “We stared at the pale man who stood in the standing-room section of the opera-house, just like ourselves, while Brahms sat in a box like God sitting on the clouds.”

". . . a leftover of old remains, not a living creature in the mainstream of the time."By 1879, Johannes Brahms was already Wolf's enemy after telling the ambitious young composer that he needed lessons in counterpoint.

Around this time, on the cusp of his maturity which was to result in the Mörike songbook, the Goethe Lieder, the Italian and Spanish Song Books, plus several attempts and one completed opera on the subject of the Three-cornered Hat (Der Corregidor), Wolf turned to purely instrumental music. Unusually, he appeared to work without benefit of a text. In May 1887, he wrote a short single-movement Serenade for string quartet in just three days. Three years later he began to refer to it as his Italian Serenade, a title that stuck when he published an arrangement for small orchestra in 1892. The piece, which the Lafayette Quartet bring to their MusicTORONTO recital later this month, starts cheerfully enough with the first violin giving the impression of still tuning –

This would find an echo the following year in a song that Wolf wrote to words by Eichendorff with a similar title, Das Ständchen (The Serenade) –

The English musicologist Eric Sams (think of him as a musical detective) has traced further connections between the Eichendorff settings that Wolf was writing at the time. But what intrigues me more is his suggestion that there’s also a literary source – a novella by Eichendorff – that gave the composer a skeleton on which to hang his serenade. It’s a romantic work of ironic self-parody titled From the Life of a Good-For-Nothing in which its anti-hero, a violinist like Wolf himself, leaves home to find fame and fortune, again like Wolf himself. The ironic edge to Eichendorff’s short story finds an echo in much of Wolf’s Serenade, which speaks with a voice that is forward-looking, of its time and never sentimental for the old days when serenades were said to be played beneath every maiden’s balcony. It also explains two over-the-top moments when the cello appears to profess love in three increasingly florid declarations, only to be mocked by the other strings –

Wolf’s Italian Serenade, with its supple musical lines, chirpy grace notes, dancing triplets, trills and underlying humour, seems to invite musical pictures into the mind. At one point, Eichendorff’s hero discovers his heroine after a serenade in Italy in which the heroine sings to the accompaniment of guitar. This seems to have a direct counterpart in Wolf –

Another of the serenade scenes in the Eichendorff novella includes a small orchestra, its instruments almost exactly mirroring those that Wolf was to include in his 1892 arrangement. The extent and scope of the scenario that Wolf draws from the Eichendorff story, perhaps, explains why Wolf wished to add additional movements to his serenade. He began several, even after insanity condemned the composer to an asylum in 1897. None, however, was ever completed. So the single-movement Serenade is all that remains of a project that appears to have remained percolating in Hugo Wolf’s mind for a quarter of a century.

Lafayette Quartet – Wolf, Shostakovich, Brahms. Thursday January 19, 2012 – 8:00 pm. Jane Mallett Theatre, St. Lawrence Centre for the Arts, 27 Front Street East, Toronto

“Conversations With Keith” featuring the Lafayette Quartet, Penderecki Quartet and New Zealand Quartets discussing Beethoven’s string quartets. CLICK for Part One CLICK for Part Two