In Search Of . . . Florence Beatrice Price (1887-1953)

October 09, 2022

“Unfortunately the work of a woman composer is preconceived by many to be light, frothy, lacking in depth, logic and virility.

Add to that the incident of race — I have Colored blood in my veins — and you will understand some of the difficulties that confront one in such a position . . .

I ask no concessions because of race or sex, and am willing to abide by a decision based solely on [the] worth of my work.

Will you be kind enough to examine a score of mine?”

That’s Florence Price in November 1943, at the age of 56 writing a third letter to Serge Koussevitzky, music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, and a well-known advocate for American music, asking him to consider performing her scores.

No performances resulted from her letters sent over a nine-year period, 1935-44.

The music of this intriguing, fascinating American composer – a composer whose music invites wide exposure – features prominently in the opening concerts of the MusicTORONTO Piano and Strings Series this season.

The Pacifica Quartet opens the Strings series with Price’s G major Quartet (1929).

And Michelle Cann, who both studied and now teaches at the Curtis Institute, performs Price’s prizewinning E minor Piano Sonata from 1932.

I have been asked to write increasingly about Price over the past five years or so, particularly during the Pandemic when musicians had time to take on new repertoire. In the meantime, a new generation has already caught up.

A timely book was published last year by Schirmer (who also hold rights to Price’s music). It was written and illustrated by Middle School students at Kaufman Music Center’s Special Music School, a K-12 NYC public school that teaches music as a core subject.

“In classical music there isn’t a lot of diversity, and being a woman of color myself, it’s inspiring to see somebody who’s made it out there,” says 14-year-old violinist and co-author Rebecca Beato. “I think it’s important to learn about Florence Price’s music and share it with the world.”

FLORENCE PRICE . . . A TIMELINE

- 1887 April 9, Florence Beatrice Smith is born in Little Rock, Arkansas to a singer/pianist mother who also has business interests and the city’s only African American dentist father. The family lives comfortably and is well respected. Composer William Grant Still, eight years younger, grew up as a neighbour.

- 1891 Gives her first piano recital.

- 1898 Publishes her first piece.

- 1901 Graduates from high school at 14, valedictorian of her class.

- 1903 Enrols at New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, majoring in piano and organ, listing her hometown as ‘Pueblo, Mexico,’ to avoid overt racial prejudice.

- In private lessons, composer and Conservatory director George Whitefield Chadwick encourages her to incorporate African American folk melodies and rhythms into her compositions.

- 1906 Graduates in three years (not the usual four) with honours, aged 19.

- 1910 Teaches as Head of the music department at Clark College in Atlanta.

- 1912 Marries civil rights attorney Thomas J Price in Atlanta, but the couple moves back to Little Rock where Price composes and teaches privately. Refused admission to the all-white Arkansas Music Teachers Association, she also teaches music at segregated black schools.

- 1927 Racial riots following a high-profile murder and a lynching forces 400 Black people to leave Little Rock. The Price family, now including two daughters, relocates to Chicago. Price pursues further education at the American Conservatory and the Chicago Musical College.

- 1928 The G. Schirmer and McKinley music publishers begin to release Price’s songs, piano pieces and instructional keyboard music.

- 1931 With Thomas Price losing his job in the Great Depression and becoming abusive, Florence files for divorce after nearly 20 years of marriage. Price, now a single parent, moves in with the Bonds family, prominent in the Chicago music community. Gives Margaret Bonds, a gifted musician, still in her teens, encouragement and lessons in composition. The two will collaborate throughout the 1930s.

- 1932 Wins overall prize in the Rodman Wanamaker Music competition with her Symphony No. 1, in E minor and first prize with the Piano Sonata in the same key.

- 1933 Her symphony is performed at the Chicago World’s Fair by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Frederick Stock, making Price the first Black woman to have her music performed by a major symphony orchestra.“

- It is a faultless work, a work that speaks its own message with restraint and yet with passion . . . worthy of a place in the regular symphonic repertory,” writes the Chicago Daily News.

- Price also wins Wanamaker Honorable Mentions for her tone poem Ethiopia’s Shadow in America and, in the piano category, her Fantasie nègre No. 4, in B minor (which Michelle Cann also includes in her MT recital).

- 1933 Composer John Alden Carpenter sponsors Price for membership in ASCAP (American Society of Composers, Authors, and Performers).

- 1934 Her music is regularly performed in churches and community settings of all sizes by many groups including the Chicago Treble Clef Glee Club which she directs, the Florence B. Price A Cappella Chorus, the Chicago Women’s Symphony and the WPA Symphony of Detroit.

- Price is also an active member of NANM (National Association of Negro Musicians).

National Association of Negro Musicians,. Board members in 1941. Florence B Price (far right) Left to Right: Blanche K. Thompson, Josephine Inness, Henry L. Grant, Mary Cardwell Daw

- To support her family, Florence composes popular songs under the name Vee Jay, plays organ in the movie houses, and orchestrates for WGN radio.

Adoration (1951) was originally written and published in 1951 for organ, though I wonder whether it had an earlier life as a song perhaps?

Its beautiful, life affirming melody has provided solace for many during the pandemic and carried the name of Florence B. Price around the world (as a quick search on YouTube will reveal).

- Many of her works are taken up by bands, women’s organizations, and smaller symphony orchestras.

- 1939 Price’s exuberant arrangement of My Soul’s Been Anchored in de Lord is performed by Marian Anderson on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in front of an integrated audience of 75,000, and on national radio, on Easter Sunday.

- 1943 Price writes her November 6 letter to Serge Koussevitzky quoted at the top of this post, seeking wider support than that given by Frederick Stock at the Chicago Symphony.

- 1951 Sir John Barbirolli commissions a Suite for strings, incorporating traditional spirituals, for the Hallé Orchestra in England. Ill health prevents Price attending the première.

- 1953 Dies June 3, 1953 in Chicago from a stroke.

- 2009 Dozens of Price’s manuscripts thought lost are found in St. Anne, Illinois in a summer house about to be renovated. These include her two violin concertos and Fourth Symphony.

- 2018 Music publisher G. Schirmer acquires rights to Price’s complete catalogue.

- 2019 Schirmer acquires another cache of previously undiscovered manuscripts, purchased at an auction located close to the 2009 manuscripts, by a private collector

- 2021 Website https://florenceprice.com/ goes online

- 2022 Both Oxford and Cambridge University Presses have books on Price in progress: Master Musicians Series, OUP and The Cambridge Companion to Florence B Price, CUP. These should throw new light on Florence Price’s substantial output of over 450 works, including 4 symphonies, a piano concerto and Rhapsody, two violin concertos, several tone poems, choral pieces, over 100 songs and arrangements, plus many works for piano, for strings, and for organ. Much of this music is only now beginning to be published and is constantly being reviewed and seen under a new lens as time and social awareness evolve. As Alex Ross wrote in The New Yorker in February 2018, “not only did Price fail to enter the canon; a large quantity of her music came perilously close to obliteration. That run-down house in St. Anne is a potent symbol of how a country can forget its cultural history.”

The Pacifica Quartet plays Florence Price’s Quartet in G major, October 13, 2022

Michelle Cann plays Price’s Sonata in E minor and Fantasie nègre No. 1, No. 2, and No. 4, October 25, 2022

Text © copyright 2022 Keith Horner. Comments welcomed: [email protected][/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column]

[/et_pb_row]

[/et_pb_section]

| Tags: Adoration, black composer, Fantasie nègre, female composer, Florence Beatrice Price, Florence Price, Margaret Bonds, Marian Anderson, My Soul’s Been Anchored in de Lord, National Association of Negro Musicians, Piano Sonata in E minor, Rodman Wanamaker Music competition, Symphony in E minor | More: Piano Series, Strings

On the trail of . . . Louis Jullien

January 19, 2021

A Quadrille-in-words, dancing to the beat of a once famous conductor and composer, also being the tale of a concert ticket to one of Jullien's renowned 'Concerts Monstres.'

Now that we’re approaching the 209th anniversary of the birth and 161st anniversary of the death of a long-forgotten conductor and composer who was once a household name throughout the UK, Paris, Dublin and even several cities in the USA, it’s high time to meet and celebrate Louis Jullien . . . .

Here we have a Thomas Beecham before Beecham. An Arthur Fiedler before Fiedler – and a lot more! Impressario, showman-conductor, and establisher of the Promenade Concerts in England, Jullien has been a companion of sorts to me for a half century.

A framed playbill for a concert culminating Jullien’s hugely popular five seasons of Promenade Concerts at the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden hangs in my study.

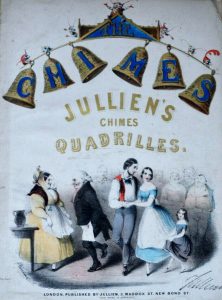

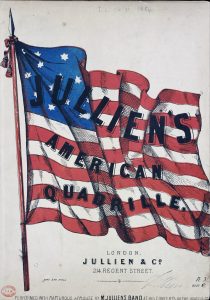

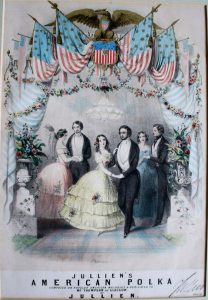

Framed, eye-catching, hand-tinted sheet music covers of a volumninous output of quadrilles, polkas, waltzes and other dances hang on other walls of my home.

Back in 1973, I researched and penned the entry in the then Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians. It’s still there in the current online dictionary (Oxford Music Online).

Jullien published ‘The Celebrated Polka’ many times from 1841 onwards. My own copy is titled ‘The Original Polka’

Jullien was a larger than life character whose declared aim was “to ensure amusement as well as attempting instruction, by blending in the programmes the most sublime works with those of a lighter school.” (Illustrated London News, November 9, 1850).

His audience was the one-shilling public.

Nevertheless, as early as his first London season he gave at least four complete Beethoven symphonies.

The more substantial fare appeared in a musical sandwich, of quadrilles, instrumental solos, galops, waltzes, popular overtures and excerpts from the favourite symphonies.

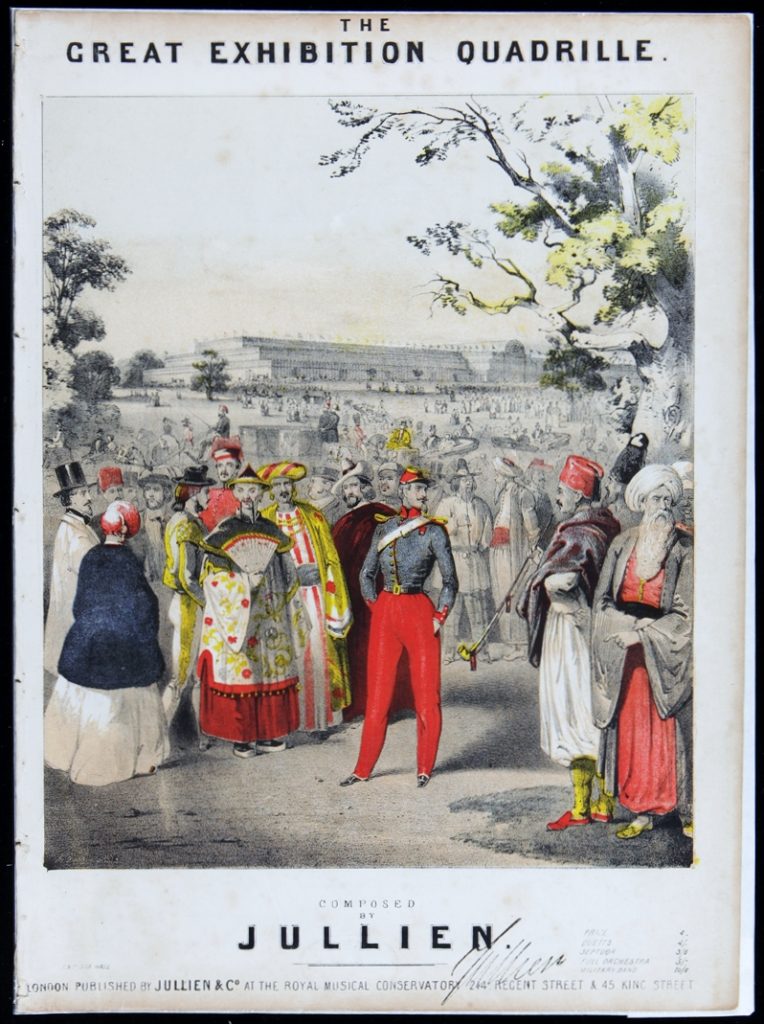

Jullien’s Great Exhibition Quadrille (1851), with the temporary Crystal Palace in London’s Hyde Park on the horizon

Pride of place in a Jullien programme went to the season’s quadrille, often based on a topical theme:

* the Great Exhibition Quadrille (1851)

* the British Navy Quadrille (1845)

* the Swiss Quadrille (1847)

* and – perhaps the most celebrated of all – the British Army Quadrille for orchestra and four military bands (1846).

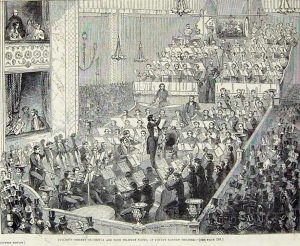

Louis Jullien conducting the ‘British Army Quadrille’ for orchestra and four military bands at Covent Garden Theatre (Illustrated London News, November 7, 1846) CLICK TO ENLARGE

Louis Jullien held a sure command of all the orchestrator’s tricks-of-the-trade, giving a surface charm to what was often second-rate music.

Occasionally it led to excesses, such as the four ophicleides, saxophone and side drums that decorated Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony.

Jullien was born in Sisteron, Basses Alpes, France, April 23, 1812.

His destiny to be considered something of a child prodigy by his violinist-bandmaster father Antonio seemed inevitable after his baptism.

The 36 male members of the Sisteron Philharmonic Society all insisted on becoming godfather to the infant Louis.

So the future conductor was blessed with enough forenames to fill a musical score – and to provide a wealth of pseudonyms when publishing his own music later in life.

Jullien's legal name:

Jullien, Louis George Maurice Adolphe Roch Albert Abel Antonio Alexandre Noé Jean Lucien Daniel Eugène Joseph-le-brun Joseph-Barême Thomas Thomas Thomas-Thomas Pierre Arbon Pierre-Maurel Barthélemi Artus Alphonse Bertrand Dieudonné Emanuel Josué Vincent Luc Michel Jules-de-la-plane Jules-Bazin Julio César

(b Sisteron, France, April 23, 1812; d Paris, March 14, 1860)

Jullien served in the army before entering the Paris Conservatoire around 1833. He left in 1836, preferring dance music over counterpoint and having no diploma or official credit.

For the next three years, Jullien’s lively entertainments of dance music at the Jardin Turc brought rapid popularity, rivalling Musard’s, and three duels brought notoriety.

Insolvent, he speedily left Paris for England in 1838.

Jullien’s first concert there was at the Drury Lane Theatre (June 8, 1840), in a series of ‘concerts d’été.’

Over the following 19 years Jullien’s activities comprised at least 24 promenade concert seasons in the London theatres, four summer seasons, notably of Monster Concerts at the Surrey Zoological Gardens, one and often two provincial tours each year, numerous engagements at balls and private social functions, plus a season of grand opera (1847).

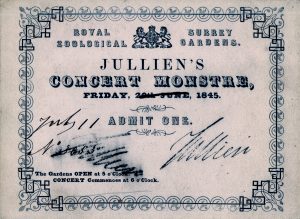

Julllien was no stranger to bankruptcy. But before we get there, I want to focus in on one of his many London concerts, a Monster Concert at the Royal Surrey Zoological Gardens in 1845, when Jullien was in his prime.

Years ago, I purchased a ticket for the occasion (I was unable to attend, being more than a century too young).

What’s particularly interesting about this ticket is that the original date, Friday June 20, is manually struck out and July 11 inserted in its place. The ticket is also manually numbered and stamped by Jullien.

[Signing tickets and sheet music was his usual practice.

As he puts it on one of my concert playbills –

” . . in order to secure the public against the possibility of purchasing incorrect copies, he has attached his signature to each – none can therefore be relied on which have not his autograph.

Correct copies to be had at all respectable music shops in the Kingdom”].

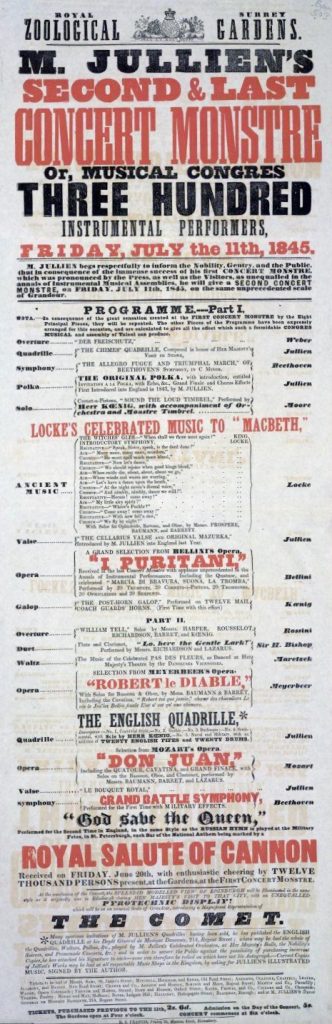

I recently – remarkably – tracked down online a playbill advertising this very concert, July 11, 1845.

“M. JULLIEN begs respectfully to inform the Nobility, Gentry and Public that in consequence of the immense success of his first CONCERT MONSTRE, which was pronounced by the Press as well as the Visitors, as unequalled in the annals of Instrumental Musical Assemblies, he will give a SECOND CONCERT MONSTRE on Friday July 11, 1845, on the same unprecedented scale of Grandeur.”

So, back to my ticket – rather than have a new date set in type, Jullien simply printed additional June 20 tickets and endorsed each of them with a new date, a hand-written ticket number and a stamped signature.

Pre-purchased tickets cost 2s 6d (a half-crown), while tickets at the gate cost 5s.

The music played ranged eclectically from the 17th century English composer Matthew Locke to Weber, Bellini, Meyerbeer, Jullien himself, a selection from Mozart’s Don Giovanni, Beethoven’s ‘Battle’ Symphony ‘with military effects.’

Rounding out the whole occasion, the bill reads –

“‘God save the Queen’, performed for the second time in England, in the same style as the Russian hymn is played at the military fetes, in St. Petersburgh, each bar of the national anthem being marked by a royal salute of cannon received on Friday, June 20th, with enthusiastic cheering by twelve thousand persons present, at the Gardens, at the first concert monstre … pyrotechnic display! … ”

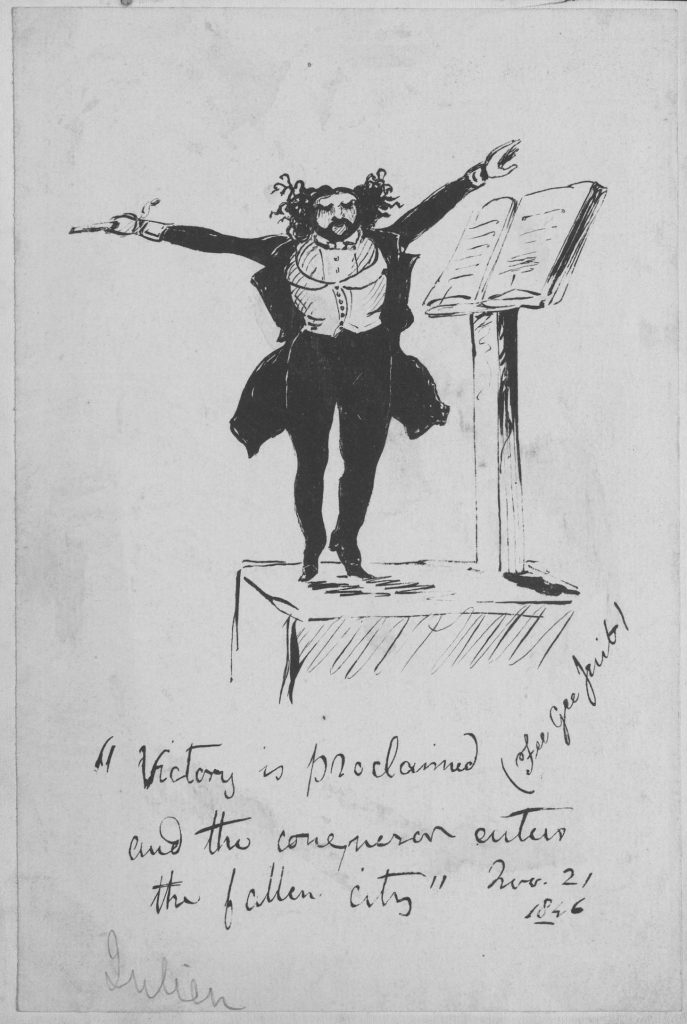

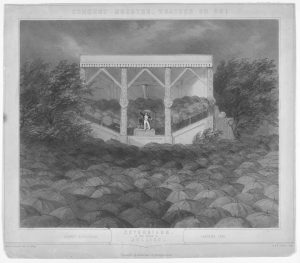

The captions on this now faded, witty cartoon read:

“Concert Monstre. Weather or No!

Surrey Zoological Gardens 1845

Enthusiasm in the reign of Jullien”

Shows Jullien in a yellow waistcoat on the podium, amid a sea of black umbrellas, held by both orchestra and audience, not a face visible!

Jullien had a shrewd eye for publicity and the serio-comic.

He undeniably educated the public during his career, but he was no reformer.

His success was due to his creating new trends and being in the vanguard.

He became a household name and, as a target for the caricaturists, rivalled the leading politicians.

But Jullien’s regular appearances in Punch, where he was referred to as ‘the Mons’, were seldom to his detriment.

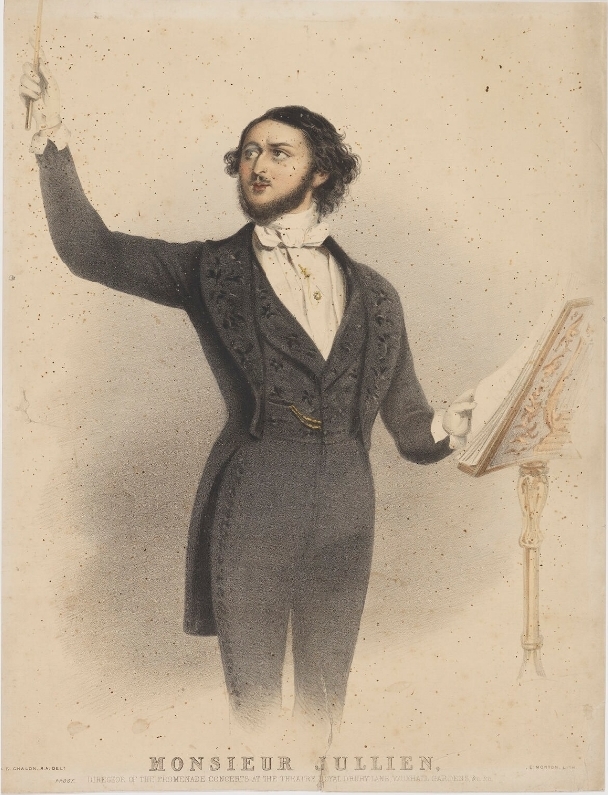

His dress was that of the dandy: raven locks, superb black moustache, coat widely open over gleaming white waistcoat and elegantly embroidered shirt-front.

His red velvet and gilt chair and elaborately decorated music stand were even taken on tour.

He conducted Beethoven with a jewelled baton handed to him on a silver salver.

This cult of the conductor was new.

Behind the pantomime and showmanship lay authority, and Jullien was a pioneer in conducting with the baton. He was able to attract the best of the London players into his orchestras and retained a team of first-class soloists over a number of years.

Berlioz’s grimly amusing account describes him as fundamentally honest but with “the incontestable character of a madman.”

A publishing business started in 1844 had to be sold to pay off debts.

The production – at his own cost – of his reputedly extravagant opera Pietro il grande at Covent Garden in August 1852 was withdrawn after five performances. No one had a good word to say about the work.

“Was that thunder?” a headline read in a review of the opera. “No! It was only Jullien’s opera.”

His personal finances had been in rough shape for years.

It was time to see what America had to offer!

A series of Farewell Concerts throughout the English provinces, Dublin and Scotland was followed by a Testimonial Concert in London.

Services were donated by loyal musicians and singers and the event culminated in the presentation of a jewel encrusted gold and maplewood baton.

It was inscribed: “Presented to M. Jullien by the members of his orchestra, the musical profession of London, and 5,000 of his patrons, admirers and friends, July 11, 1853.”

Jullien took with him principals and core players from his London orchestra, two instrumental soloists (Koenig and Bottesini) and two vocalists.

There were 30 musicians in all – plus 11 TONS of baggage!

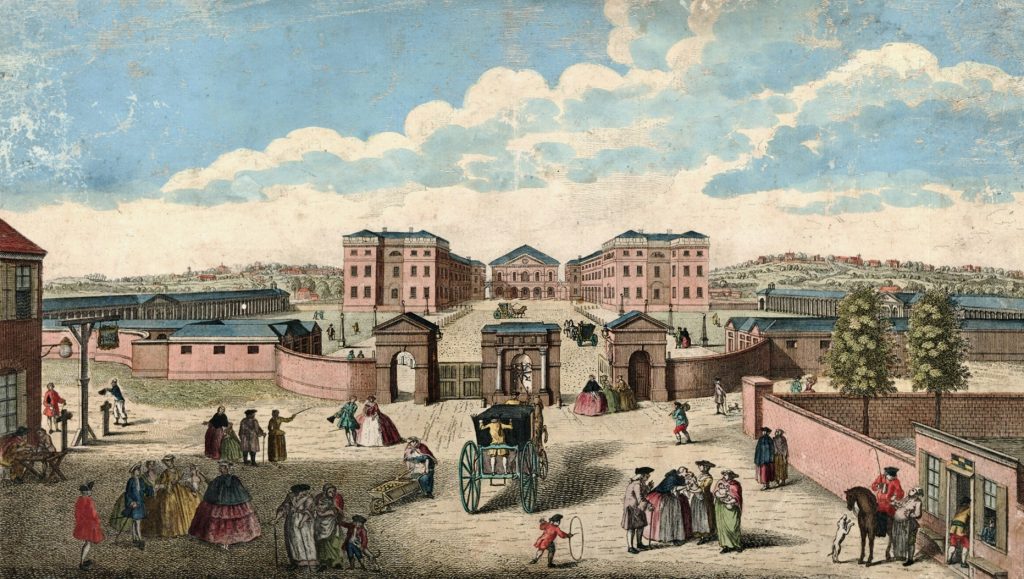

New York’s Castle Garden, accomodating 10,000, was the site of the first month’s concerts.

With the orchestra beefed up to 100 with New York’s finest musicians, the public and even the music critics were enthusiastic over Jullien’s mix of classical favourites and virtuoso solo turns, quadrilles, polkas, waltzes and the like.

“Jullien is the strategist of musical art; he deals in vast masses of sound; he collects and gives unity to a hundred different airs, played by as many instruments.”- Wall Street Journal.

“Great is Jullien, and great will be his profits!”- The Spirit of the Times.

“If he plays quadrilles, it is because a man of genius can put his genius into a quadrille as well as into a mass or a symphony, and a good quadrille has more merit than a mediocre mass or symphony.”-New York Tribune.

Three weeks in New York’s Metropolitan Hall brought even more fulsome praise, followed by more concerts along the Eastern seaboard and, early in 1854, even further afield.

In all, Jullien gave 214 concerts in the US, receiving $15,000 per month from the four investors who bankroled the venture.

By way of comparison, his star soloist, double bass virtuoso Giovanni Bottesini, received a handsome $1,000 per month and other soloists proportionately lucrative profits.

After a year away from home, Jullien threw himself into more promenade seasons at the Drury Lane Theatre and Covent Garden, with another tour to Scotland and Ireland. He also gave concerts in Paris, Holland and Belgium, where he had bought a chateau.

In the midst of all this activity there was a disastrous fire at Covent Garden in 1856 in which scores and parts for all Jullien’s major works were destroyed.

Then, the following year, Jullien lost heavily in the collapse of the Surrey Garden Company, now transformed from public pleasure garden with an open-air stage to handsome New Music Hall accomodating 10,000, set amid graceful gardens.

After another round of Farewell Concerts in London and the provinces (1858–9, playing his Hymn of Universal Harmony everywhere), Jullien arrived back in Paris in May 1859.

Plans for a huge ‘Universal Musical Tour’ were abandoned and reports from Berlioz among others described his increasing instability.

As was customary throughout his life, various tales swirl around Jullien’s tragic final weeks.

These are bookended by a documented three months in a Paris debtor’s prison in 1859 and a few days in the Neuilly Maison de Santé, where he died March 14, 1860.

His English-born wife (name unknown), who ran a flower stall at her husband’s promenade concerts, outlived him. She was employed at the box office at the Drury Lane Theatre after his death.

Their only son, Louis, conducted promenade concerts (somewhat unsuccessfully) at Her Majesty’s Theatre in 1863 and 1864.

In the democratization of music and the establishment of the early promenade concert, Jullien’s role was significant.

Natural reserve and reaction against flamboyance by the musical establishment may account for some of the grudging contemporary accounts of his achievement.

English music critic William Davison, however, was a supporter and personal friend: “M. Jullien,” he wrote in an obituary in the Musical World, “was undoubtedly the first who directed the attention of the multitude to the classical composers … [he] broke down the barriers and let in the ‘crowd’.”

Contents © copyright 2021 Keith Horner. Comments welcomed: [email protected]

| Tags: British Army Quadrille, Castle Garden New York, Concert monstre, conductor, Drury Lane Theatre, Great Exhibition Quadrille, Hymn of Universal Harmony, Louis Jullien, Louis-Antoine Jullien, Monster Concert, Pietro il grande, promenade concerts, Royal Surrey Zoological Gardens, Sisteron, Sisteron Basses Alpes | More: Uncategorized

On the trail of . . . Handel’s Messiah (audio documentary)

December 16, 2020

Hallelujah: The Making of Handel’s Messiah

A two-hour radio documentary by prize-winning documentary producers Keith Horner and Steve Wadhams celebrating and illuminating Handel’s masterpiece.

This wide-ranging, two-hour, radio documentary interweaves experts talking about Messiah with a small-town choir from Parry Sound, Ontario preparing to present Messiah for the very first time.

• Producers Horner and Wadhams travel to Dublin to discover where Messiah was first performed in 1742.

• Conductor Christopher Hogwood analyses the work at his harpsichord.

• Scholar Donald Burrows tours the Handel monuments and opens original Handel scores in London and Oxford.

• Colin Masters unlocks the vaults of the Thomas Coram Foundation (the Foundling Hospital), in London.

• Ruth Smith talks about Charles Jennens, who compiled the text of Messiah.

• Other experts interviewed on location include Emma Kirkby, Ivars Taurins, Nicholas McGegan, Bryan Boydell, and Walter Hewlitt from the Center for Computer Assisted Research into the Humanities in California.

• Enjoy and please add comments!

| More: Uncategorized

On the trail of . . . Handel’s Messiah

December 13, 2020

“It’s impossible to kill the beast!” the late conductor Christopher Hogwood told me almost 30 years ago.

“I’ve even conducted a staged performance in Germany,” he added, eyes rolling mischievously, as he described what was then a novelty.

2020 will find Messiah as resilient and open to change as ever, as it is re-invented and re-imagined . . . with more than a little help from the internet.

English music historian Charles Burney presciently seemed to foresee Messiah’s potential for change when he reported, just 40 years after the work’s premiere:

“This great work has been heard in all parts of the kingdom with increasing reverence and delight.

It has fed the hungry, clothed the naked, fostered the orphan and enriched succeeding managers of the oratorios, more than any single production in this or any other country.”

When I last saw Handel’s draft score of Messiah in the British Museum, it was positioned, with a curator’s sense of the improbable, between a copy of the Magna Carta and a collection of The Beatles’ manuscripts.

Lasting well over two hours in performance, it took the 57-year-old composer a little over three weeks to compose in 1741.

Plaque at 25 Brook St, Mayfair now home of the Handel House Museum, where Handel wrote Messiah, with today’s Georgian period houses opposite

Handel was a professional man of the theatre, a fast and fluent writer. He could immerse himself in the composition of a work, thinking clearly and precisely from the beginning of a movement to the end, seldom pausing to correct or revise a phrase.

Still, for all its fluency and orderliness, the autograph score of Messiah tells only part of the story. It differs from what we hear in a present-day concert performance or on CD.

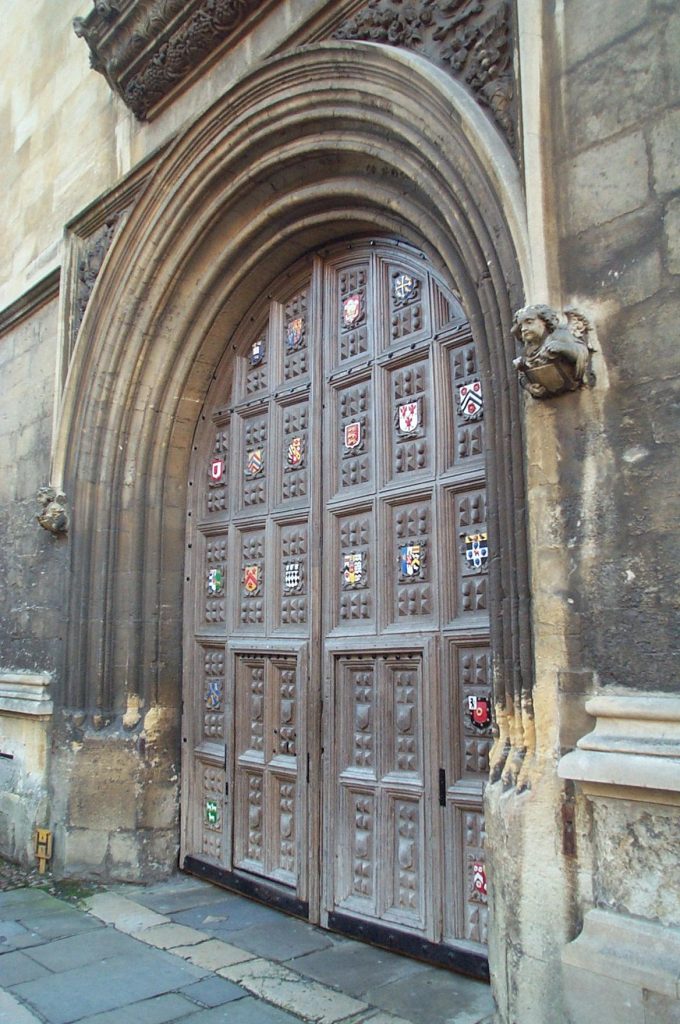

Another score, now residing among the 13 million items of the Bodelian Library in the English university city of Oxford tells a further chapter in the story.

This is Handel’s own conducting score, made by one of a team of music copyists shortly after Messiah was first written.

We can tell from pencilled names in the score that Handel would have as many as eight soloists at his disposal one year, five or six the next – but only once, it appears, the by now customary four soloists. As the skills of his singers varied, Handel noted variants in the vocal line in different coloured ink.

Looking through this well-thumbed manuscript in the Bodleian Library, another piece of the puzzle begins to fall in place.

Handel clearly wrote Messiah as a blueprint. It is a very adaptable work, designed with a master craftsman’s skill to be performed by different soloists, instrumentalists and singers.

It follows that there is no single ‘correct’ way of performing Messiah. Musicians have alternatives to chose from. It’s possible to recreate the very first performance of Messiah in Dublin, the first London performance at Covent Garden in 1743, or the series of performances Handel gave at the Foundling Hospital in London.

Messiah is structured with great forward momentum and careful tonal relationships throughout. Each section – or ‘scene’- culminates, after a series of ascending recitatives and arias, in a chorus.

Before long, Messiah had been appropriated by both Church and State. The reasons for this worked at several levels:

Handel’s music had wide appeal because the focus of attention had moved away from the solo recitative and aria of the opera house to the chorus, a clear attempt to capitalize on the popular success of his own anthems.

In England, the chorus represented ‘people power’ for a nation of shopkeepers who had a tough time with the excesses of Italian opera. The sentiments of the text strengthened the imperial ambitions of their masters.

They sang “And He shall reign for ever and ever, King of Kings and Lord of Lords,” in near-tribal affirmation of Britannia ruling the waves.

Small wonder that George II was reputed to have jumped to his feet in awe of Handel the composer, God the Creator and – the crowning touch – himself as the Empire-builder with the divinely given power to reign for ever.

The compiler of the text was the much-maligned Charles Jennens, a wealthy landowner, usually portrayed as a vain, self-important fool.

Jennens, however, was a highly intelligent man, who was able to provide a structure and a text for Messiah which Handel almost certainly followed without significant alteration.

Jennens knew his Bible from cover to cover. His collection of religious books was one of the best in the land. He possessed a magpie-like ability to combine texts from the prophets, from the New Testament and from the Book of Common Prayer with single-minded purpose.

His text does not follow the familiar New Testament story of Christ and his disciples, as would an opera libretto. It essentially approaches the subject through the thoughts of the prophets, as an abstract idea and not as the human drama of the evangelists.

In so doing, Jennens’ text focuses on the mystery of God’s redemption of mankind through his Messiah. Messiah, a Hebrew word is significantly the title of the oratorio, not Christ, its New Testament Greek equivalent.

Jennens’ objective was to assert specific religious beliefs: beliefs that were to isolate him from the mainstream of English religious – and thus social – life. His thinking anticipated the High Church movement of the 19th century, asserting the mystery of God’s ways in an age that was increasingly rationalist.

As a non-juror, he refused to swear allegiance to the crown, to William and Mary, the Hanoverian succession to the house of Stuart. That said, boosterism of the monarch was, in fact, the opposite of what Jennens had on his mind when compiling his text for Handel.

By avoiding direct narrative in the sung words, both Jennens and Handel knew that they were more likely to avoid offending religious sensibilities when the work was first performed. And this proved to be the case in Dublin on April 13, 1742.

Why Dublin? you might reasonably ask.

The truth is that Handel’s fortunes were at a low ebb that previous year.

As a commercial undertaking, Handel’s beloved opera seria had not been a success. As his own impresario, he was running up against factious divisions in a public whose support he needed. He was even considering returning to the Continent to try his fortunes away from the country he had adopted for the past 30 years.

Then came an invitation to ‘lead the music season’ by producing operas and concerts in the city of Dublin, then the second largest city in the British Empire.

There was a public rehearsal of Messiah April 9, 1742. Positive reception in the Dublin press suggested that the work was destined to become a huge success.

The premiere followed on April 13, as a beneft “For Relief of the Prisoners in the several Gaols, and for the Support of Mercer’s Hospital in St. Stephen’s St., and of the Charitable Infirmary on the Inns Quay.”

There was a further public performance June 3.

Newspaper announcements requested that ladies came without hoops and gentlemen without swords in order to accomodate more people – and raise more money.

Fishamble St gentrified. The Music Hall gateway remains, leading to a memorial garden, with a statue of Handel.

The Chorus Cafe (behind car) serves good food and coffee.

The Georgian Kennan and Sons building is nicely preserved.

The Handel Hotel (far right) – ?? send me a review!

A choir sings choruses from Messiah right here, outside, on Fishamble St. every April 13.

£400 was raised for charity. 142 men were released from debtor’s prison The seeds for the popular success of the work were sown.

But Handel was cautious. London had to wait a year to hear Messiah.

Rightly so, as it turned out because it was not till 1750 that Messiah was accepted into a position of total respectability by the Establishment.

Annual performances of the work at the Foundling Hospital, given for the benefit of the oldest registered charity in Europe, would ensure the utmost respectability for all performances of the oratorio whether in church, chapel or theatre.

The precedent for performances at Christmas, as well as the then customary Lent (when theatres were closed), was now established – and it was to stick!

“Yes, there was some method in his madness, if I can put it that way,” a former director of the Thomas Coram Foundation, as the Foundling Hospital is now known, told me a few years ago.

“Handel’s concerts for the Foundling Hospital gave us financial help when we needed it – over half a million dollars’ worth in all, I estimate. But I’ve no doubt that there was a benefit for him too. Today, you’d say it was a symbiotic relationship.”

This was to prove the winning combination.

Messiah manages at once to represent deep religious values with its text drawn from the Bible. Through his music and through Christ’s story – from the prophecy of the birth of a Messiah and his life, the Passion and the Resurrection, and Christ’s glorification in Heaven – Handel’s skill as a composer succeeds in representing man’s lot in a positive, self-affirmative way.

Its rousing music even takes that affirmation a stage further towards both spiritual and material identification on the part of the listener.

And this stirring affirmation in the name of God, Man and, maybe, King/Queen or State is all for a noble cause!

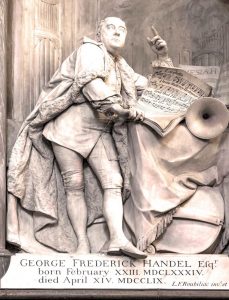

Handel himself was, at his own request, crowned with a final resting place in Westminster Abbey.

Today, as we look up at Roubiliac’s statue, some 12 feet above ground level, Handel himself looks up, symbolically, to heaven, an angel above his head, an organ behind his body, and a scroll of music in his hand containing both music and words of a movement from Messiah, his best-loved work.

It reads “I Know that My Redeemer Liveth.”

Text © copyright 2020 Keith Horner. Comments welcomed: [email protected]

| More: Uncategorized

On the trail of . . . Chopin in Mallorca

June 20, 2020

For decades I’d read about an abandoned 13th. century Carthusian monastery to which Fryderyk Chopin and his lover George Sand retreated, far away from the prying eyes of Parisian society. The atmosphere it evokes, both from Sand’s pen and from a number of biographers, sounded so quintessentially romantic.

Legend has it that while staying in one of its monk’s cells, Chopin heard the unceasing dripping of rain water throughout the day and night while completing his collection of Preludes. This inspired the so-called Raindrop Prelude, Op. 28 No. 15, the longest piece in the collection and an anchor and focal point, with its evocative, timeless, nocturnal dreaming.

Now here in front of me, exactly 180 years later, early one December morning, is that monastery and former royal residence, looming large and rather forbidding, with its austere facade. What, I wondered, lies beyond those walls?

Our journey has taken us from Barcelona on the Spanish mainland to the island of Mallorca (Majorca) – certainly with more comfort than that of Chopin, Sand, her two children Maurice (then 15) and Solange (10), plus a maid, Amelia.

They sailed from Barcelona on the El Mallorquin, a steamer primarily designed to transport a cargo of 200 black Mallorcan pigs every week to the markets of Barcelona.

That dubious pleasure lay ahead for the party on what would become a hastily arranged retreat from the keenly anticipated comforts of the Mediterranean island.

On arriving on the island, in Palma November 8, 1838 at 11:30am, there were no inns to be found (none on the island at all, if Sand’s colourful, though malicious travel memoir Winter in Mallorca (1842) can be believed – which it can’t!).

Chopin’s initial reaction to the island was also favourable.

On November 15, he wrote from Son Vent to fellow pianist Julian (Jules) Fontana in Paris.

“Here I am in the midst of palms and cedars and cacti and olives and lemons and aloes and figs and pomegranates,” he enthused.

“The sky is turquoise blue, the sea is azure, the mountains are emerald green … all day long the sun shines and it is warm, and everybody wears summer clothes.”

This was too good to be true.

The idyllic weather soon broke, Sand

recounts, and the rains started.

“The damp settled like a cloak of ice over our shoulders and reduced me to paralysis.”

On December 3rd, 1838, Chopin again wrote to Fontana:

“I have not been able to send you the manuscripts (His 24 Preludes) since they are not ready. For the past three weeks I have been as sick as a dog, despite a heat of 18 degrees, despite the roses, orange trees, palms, and flowering fig-trees. I caught a bad cold.

“The first said that I would die.

“The third that I was already dead.”

Chopin’s consumption (tuberculosis) was already being whispered about among the fearful Mallorcans. It was viewed as contagious, much like a coronovirus.

The lease on the villa was quickly broken and the property vacated by the end of the month. Sand was billed extra for a deep cleaning.

Chopin consulted his doctors while the Chopin-Sand party stayed with the French Consul in Palma.

Valldemossa today, with monastery in distance in centre, December 21, 2018, CLICK ANY IMAGE TO ENLARGE

In 1838, however, George Sand recalls a very different experience, travelling in a cartana – a kind of springless post-chaise pulled by a horse or mule:

“Ravines, torrents, swamps, quickset hedges, ditches, all bar the path in vain. One does not stop for such trifles, because, of course they are part of the road.

“And yet you often reach your destination safe and sound, thanks to the steadiness of the carriage and the strength of the horse’s legs, though one wheel may run on a mountain and the other in a ravine . . .”

Now, it would seem, in this mountain-top village in the Tramuntana range, Chopin the composer and Sand the writer would have the solitude and peace they were seeking, both for work and for health.

But what attracted the Polish composer-pianist and French novelist, memoirist and social activist to one another in the first place?

Born Amandine Aurore Lucille Dupin in 1804 (six years before Chopin), Sand acquired her pen name via one of many lovers, Jules Sandeau, with whom she co-authored her earliest publications.

“I dashed back and forth across Paris and felt I was going around the world . . . Nobody heeded me. Or suspected my disguise . . .”

Victor Hugo concluded: “George Sand cannot determine whether she is male or female . . . but it is not my place to decide whether she is my sister or my brother.”

Chopin, on the other hand, recoiled from public life.

He preferred the salon to the concert hall and composition to the gladiatorial competitiveness among the lions of the keyboard he encountered in Paris.

Fellow pianist-composer Ignaz Moscheles observed in 1839: “His appearance is exactly like his music; both are tender and schwärmerisch” (fanciful, dreamy, enthusiastic).

“Chopin was feminine in looks, gestures, and taste,” according to his pupil Adolf Gutmann.

Opposites attract and never more so than with Chopin and Sand.

They were opposites in politics, he a traditionalist, favouring the company of the aristocracy, she a full-throated child of the French Revolution, egalitarian in her views, provocatively unorthodox in her attitudes.

His ancestry was middle-class and devoutly Catholic; hers aristocratic, advantaged and liberal-minded.

Chopin was reserved in his thoughts, refined, even aloof. Sand, meanwhile, lived life like a book – and, frequently, included life’s characters, thinly disguised, in her own writings.

Today, she would have posted prolifically on social media; in 1838, her followers had to buy her books!

“Together they were to become one of the oddest couples in Europe,” says Chopin biographer Jeremy Siepmann.

The monastery’s charter-house corridors, deconsecrated in 1835, still maintain a stark simplicity today

“This is the devil’s own country as far as mail, the population and comforts are concerned,” Chopin writes days after arriving in Valldemossa.

“The sky is as lovely as your soul; the earth is as black as my heart.”

“This Charter-house has no architectural beauties, but is a series of sturdy, amply-designed buildings,” Sand writes in A Winter in Mallorca.

“Its massive walls of dressed stone enclose an area which would have sufficed to house an army corps.

Yet the whole edifice had been built for only 12 monks and their prior.

The ‘new cloisters’ alone – at various periods, three Carthusian monasteries have here been built on to one another – give access to 12 cells, each consisting of three spacious rooms.

At right angles to these cloisters run two lines of chapels, 12 in all; because each monk had his own chapel, where he used to retire for solitary devotion.”

For three generations, the Ferrá-Capllonch family claimed No. 2 as the only authentic Chopin museum in Mallorca.

A court case in 2004 – with Chopin’s piano as evidence – put an end to the feud, which endured over three generations.

In other words, for three generations, visitors to Valldemossa were tricked into paying an admission fee to be misled into believing they were in the Chopin-Sand cell. The piano they saw there was proven to have been built a decade after Chopin’s visit.

References to this museum are still, confusingly, all over the web.

Its arrival was delayed and then the high import duties required much negotation.

The piano remained in Mallorca because high export duties would have been demanded and – more importantly – Chopin’s consumption made it an object which no-one wished to handle.

The ever-resourceful author persuaded the French Consul’s chef to send provisions from Palma.

She even purchased a goat and a sheep for milk.

“Since it rained off and on for two months [December and January are the rainy season in the Balearic Islands] we frequently nibbled bread as hard as ship’s biscuit and dined like true Carthusians,” Sand wrote.

In an act of revenge, she even referred to Mallorcans as “barbarians, thieves, monkeys and Polynesian savages” in A Winter in Mallorca.

The caption, in French, reads: “Visit of the priest who explains to us what snow is (as if we didn’t already know).

“Sand was a beautiful woman, endowed with a face full of intelligence, animated by her beautiful black eyes . . .”

“Chopin was very ill. He came looking for southern weather to restore his health . . .”

CLICK THE IMAGE FOR MORE

The compact, three-room museum contains original lithographs by Chopin and Sand, letters and manuscripts (or facsimiles) related to Mallorca, medallions, sculptures and other memorabilia.

Chopin, with his small, fine-boned hand, was heard to advantage in the salon, rather than the larger concert hall. His touch was sensitive and nuanced, never forceful.

Chopin was an innovator, integrating carefully shaded dynamics, subtle use of the pedals, fresh developments in keyboard fingering and refined use of rubato that all blossomed when heard in the intimate salon.

My hand (on top of a display case (about 18 inches above the exhibits) is substantially larger than the cast made of Chopin’s left hand by Auguste Clésinger, French sculptor, painter and husband of Sand’s daughter Solange [but the tale of this marriage is a sorry tale for another day . . .]

Even in late December, the view from Cell #4 balcony is stunning.

“It is a sublime picture: the foreground framed by dark, fir-covered rocks, the middle distance by bold mountains fringed with stately trees,

the near background by rounded hillocks which the setting sun gilds warmly, and on whose crests the eye can make out, though a league away, the outlines of microscopic trees, delicate as a butterfly antennae, but as sharply black as the stroke of a pen in Indian ink on a field of sparkling gold.

Yet the sea lies still farther in the background and, when the sun returns in the morning and the plain resembles a blue lake, the Mediterranean sets a limit to this dazzling vista with a strip of brilliant silver.”

– from A Winter in Mallorca

Sand, by now, was performing heroic service to her family. She was providing the necessities of life, overseeing her maid and a hired local cook. She was teaching her children during the day, nursing the declining Chopin, and still finding energy to write by night, revising her provocative 1833 novel Lélia and completing Spiridion, a gothic novel, examining and critiquing monastic life.

Chopin then began coughing blood.

Sand made all the travel arrangements, with many odds stacked against her.

“And the reason for this unfriendliness?” Sand wrote to her friends. “It was because Chopin coughs, and whosoever coughs in Spain is declared consumptive; and he who is consumptive is held to be a plague-carrier, a leper. They haven’t sticks, stones and police enough to drive him out, for, according to their ideas, consumption is catching and the sufferer should therefore be slaughtered if possible, just as the insane were strangled two hundred years ago. We were treated like outcasts in Mallorca – because of Chopin’s cough and also because we didn’t go to church.”

They set sail for Barcelona February 14, 1839, together with 200 pigs, Chopin coughing and haemorrhaging badly.

They arrived in Mallorca as lovers; they left with a different relationship.

“I care for him like a child and he loves me like a mother,” Sand confided to Charlotte Marliani.

Chopin was nursed back to health in Barcelona, then Marseilles and, finally, at Sand’s chateau at Nohant in France.

Life in Nohant and Paris resumed, with Sand continuing to provide the secure environment Chopin needed to compose.

During their long and complex ten-year relationship, Chopin composed some of his finest works – the 24 Preludes, the B-flat and B minor Sonatas, the C-sharp minor Scherzo, F minor Ballade, the Polonaise-fantasie, and many waltzes, mazurkas, Polonaises,nocturnes and other works.

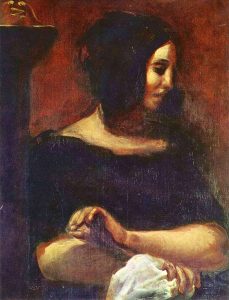

George Sand, Fryderyk Chopin, portrait after Delacroix, 1838/2008, currently in the Louvre museum.

The two lovers posed for their friend Eugène Delacroix before leaving for Mallorca. The painting was considered unfinished and remained in the artist’s possession until his death.

It was then sold several times and eventually cut into two parts,with some features removed.

The George Sand part is at the Ordrupgaard museum in Copenhagen, the Chopin part now at the Louvre.

This is a 2008 hypothetical reconstruction of the painting, based on Delacroix’s sketch and completed sections.

Stephen Hough plays music by Chopin in his January 19, 2021 concert for MusicTORONTO.

Janina Fialkowska has another Chopin set, April 27, 2021.

Blog post copyright © 2020 Keith Horner