“It’s impossible to kill the beast!” the late conductor Christopher Hogwood told me almost 30 years ago.

“I’ve even conducted a staged performance in Germany,” he added, eyes rolling mischievously, as he described what was then a novelty.

2020 will find Messiah as resilient and open to change as ever, as it is re-invented and re-imagined . . . with more than a little help from the internet.

English music historian Charles Burney presciently seemed to foresee Messiah’s potential for change when he reported, just 40 years after the work’s premiere:

“This great work has been heard in all parts of the kingdom with increasing reverence and delight.

It has fed the hungry, clothed the naked, fostered the orphan and enriched succeeding managers of the oratorios, more than any single production in this or any other country.”

When I last saw Handel’s draft score of Messiah in the British Museum, it was positioned, with a curator’s sense of the improbable, between a copy of the Magna Carta and a collection of The Beatles’ manuscripts.

Lasting well over two hours in performance, it took the 57-year-old composer a little over three weeks to compose in 1741.

Plaque at 25 Brook St, Mayfair now home of the Handel House Museum, where Handel wrote Messiah, with today’s Georgian period houses opposite

Handel was a professional man of the theatre, a fast and fluent writer. He could immerse himself in the composition of a work, thinking clearly and precisely from the beginning of a movement to the end, seldom pausing to correct or revise a phrase.

Still, for all its fluency and orderliness, the autograph score of Messiah tells only part of the story. It differs from what we hear in a present-day concert performance or on CD.

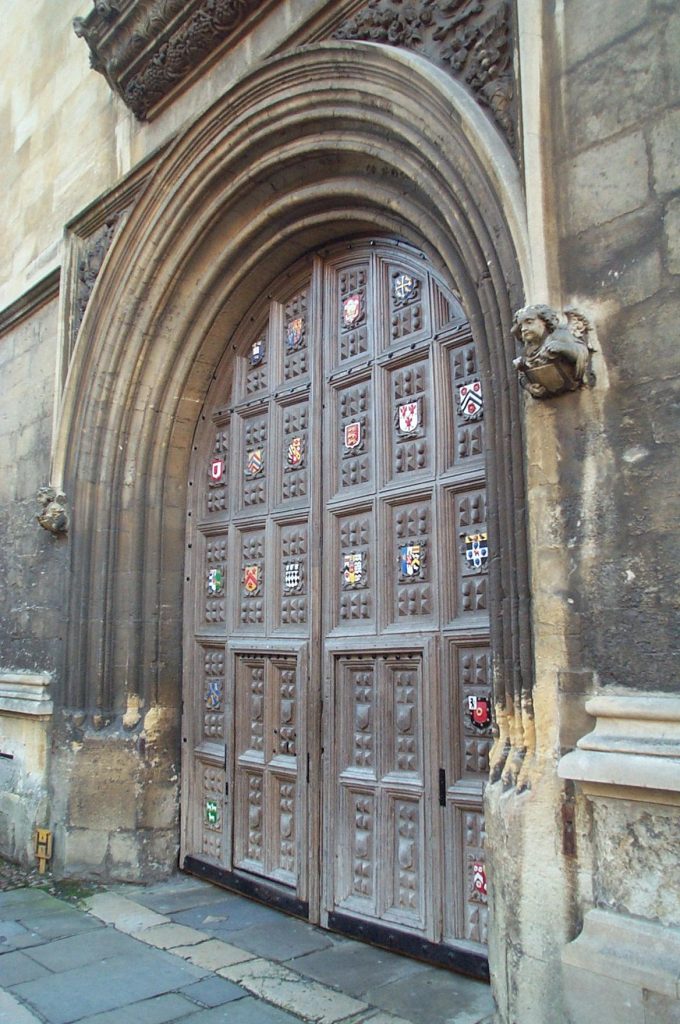

Another score, now residing among the 13 million items of the Bodelian Library in the English university city of Oxford tells a further chapter in the story.

This is Handel’s own conducting score, made by one of a team of music copyists shortly after Messiah was first written.

We can tell from pencilled names in the score that Handel would have as many as eight soloists at his disposal one year, five or six the next – but only once, it appears, the by now customary four soloists. As the skills of his singers varied, Handel noted variants in the vocal line in different coloured ink.

Looking through this well-thumbed manuscript in the Bodleian Library, another piece of the puzzle begins to fall in place.

Handel clearly wrote Messiah as a blueprint. It is a very adaptable work, designed with a master craftsman’s skill to be performed by different soloists, instrumentalists and singers.

It follows that there is no single ‘correct’ way of performing Messiah. Musicians have alternatives to chose from. It’s possible to recreate the very first performance of Messiah in Dublin, the first London performance at Covent Garden in 1743, or the series of performances Handel gave at the Foundling Hospital in London.

Messiah is structured with great forward momentum and careful tonal relationships throughout. Each section – or ‘scene’- culminates, after a series of ascending recitatives and arias, in a chorus.

Before long, Messiah had been appropriated by both Church and State. The reasons for this worked at several levels:

Handel’s music had wide appeal because the focus of attention had moved away from the solo recitative and aria of the opera house to the chorus, a clear attempt to capitalize on the popular success of his own anthems.

In England, the chorus represented ‘people power’ for a nation of shopkeepers who had a tough time with the excesses of Italian opera. The sentiments of the text strengthened the imperial ambitions of their masters.

They sang “And He shall reign for ever and ever, King of Kings and Lord of Lords,” in near-tribal affirmation of Britannia ruling the waves.

Small wonder that George II was reputed to have jumped to his feet in awe of Handel the composer, God the Creator and – the crowning touch – himself as the Empire-builder with the divinely given power to reign for ever.

The compiler of the text was the much-maligned Charles Jennens, a wealthy landowner, usually portrayed as a vain, self-important fool.

Jennens, however, was a highly intelligent man, who was able to provide a structure and a text for Messiah which Handel almost certainly followed without significant alteration.

Jennens knew his Bible from cover to cover. His collection of religious books was one of the best in the land. He possessed a magpie-like ability to combine texts from the prophets, from the New Testament and from the Book of Common Prayer with single-minded purpose.

His text does not follow the familiar New Testament story of Christ and his disciples, as would an opera libretto. It essentially approaches the subject through the thoughts of the prophets, as an abstract idea and not as the human drama of the evangelists.

In so doing, Jennens’ text focuses on the mystery of God’s redemption of mankind through his Messiah. Messiah, a Hebrew word is significantly the title of the oratorio, not Christ, its New Testament Greek equivalent.

Jennens’ objective was to assert specific religious beliefs: beliefs that were to isolate him from the mainstream of English religious – and thus social – life. His thinking anticipated the High Church movement of the 19th century, asserting the mystery of God’s ways in an age that was increasingly rationalist.

As a non-juror, he refused to swear allegiance to the crown, to William and Mary, the Hanoverian succession to the house of Stuart. That said, boosterism of the monarch was, in fact, the opposite of what Jennens had on his mind when compiling his text for Handel.

By avoiding direct narrative in the sung words, both Jennens and Handel knew that they were more likely to avoid offending religious sensibilities when the work was first performed. And this proved to be the case in Dublin on April 13, 1742.

Why Dublin? you might reasonably ask.

The truth is that Handel’s fortunes were at a low ebb that previous year.

As a commercial undertaking, Handel’s beloved opera seria had not been a success. As his own impresario, he was running up against factious divisions in a public whose support he needed. He was even considering returning to the Continent to try his fortunes away from the country he had adopted for the past 30 years.

Then came an invitation to ‘lead the music season’ by producing operas and concerts in the city of Dublin, then the second largest city in the British Empire.

There was a public rehearsal of Messiah April 9, 1742. Positive reception in the Dublin press suggested that the work was destined to become a huge success.

The premiere followed on April 13, as a beneft “For Relief of the Prisoners in the several Gaols, and for the Support of Mercer’s Hospital in St. Stephen’s St., and of the Charitable Infirmary on the Inns Quay.”

There was a further public performance June 3.

Newspaper announcements requested that ladies came without hoops and gentlemen without swords in order to accomodate more people – and raise more money.

Fishamble St gentrified. The Music Hall gateway remains, leading to a memorial garden, with a statue of Handel.

The Chorus Cafe (behind car) serves good food and coffee.

The Georgian Kennan and Sons building is nicely preserved.

The Handel Hotel (far right) – ?? send me a review!

A choir sings choruses from Messiah right here, outside, on Fishamble St. every April 13.

£400 was raised for charity. 142 men were released from debtor’s prison The seeds for the popular success of the work were sown.

But Handel was cautious. London had to wait a year to hear Messiah.

Rightly so, as it turned out because it was not till 1750 that Messiah was accepted into a position of total respectability by the Establishment.

Annual performances of the work at the Foundling Hospital, given for the benefit of the oldest registered charity in Europe, would ensure the utmost respectability for all performances of the oratorio whether in church, chapel or theatre.

The precedent for performances at Christmas, as well as the then customary Lent (when theatres were closed), was now established – and it was to stick!

“Yes, there was some method in his madness, if I can put it that way,” a former director of the Thomas Coram Foundation, as the Foundling Hospital is now known, told me a few years ago.

“Handel’s concerts for the Foundling Hospital gave us financial help when we needed it – over half a million dollars’ worth in all, I estimate. But I’ve no doubt that there was a benefit for him too. Today, you’d say it was a symbiotic relationship.”

This was to prove the winning combination.

Messiah manages at once to represent deep religious values with its text drawn from the Bible. Through his music and through Christ’s story – from the prophecy of the birth of a Messiah and his life, the Passion and the Resurrection, and Christ’s glorification in Heaven – Handel’s skill as a composer succeeds in representing man’s lot in a positive, self-affirmative way.

Its rousing music even takes that affirmation a stage further towards both spiritual and material identification on the part of the listener.

And this stirring affirmation in the name of God, Man and, maybe, King/Queen or State is all for a noble cause!

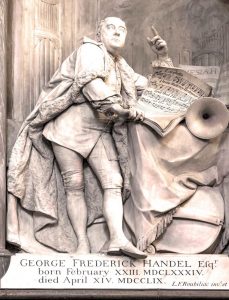

Handel himself was, at his own request, crowned with a final resting place in Westminster Abbey.

Today, as we look up at Roubiliac’s statue, some 12 feet above ground level, Handel himself looks up, symbolically, to heaven, an angel above his head, an organ behind his body, and a scroll of music in his hand containing both music and words of a movement from Messiah, his best-loved work.

It reads “I Know that My Redeemer Liveth.”

Text © copyright 2020 Keith Horner. Comments welcomed: [email protected]