A Quadrille-in-words, dancing to the beat of a once famous conductor and composer, also being the tale of a concert ticket to one of Jullien's renowned 'Concerts Monstres.'

Now that we’re approaching the 209th anniversary of the birth and 161st anniversary of the death of a long-forgotten conductor and composer who was once a household name throughout the UK, Paris, Dublin and even several cities in the USA, it’s high time to meet and celebrate Louis Jullien . . . .

Here we have a Thomas Beecham before Beecham. An Arthur Fiedler before Fiedler – and a lot more! Impressario, showman-conductor, and establisher of the Promenade Concerts in England, Jullien has been a companion of sorts to me for a half century.

A framed playbill for a concert culminating Jullien’s hugely popular five seasons of Promenade Concerts at the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden hangs in my study.

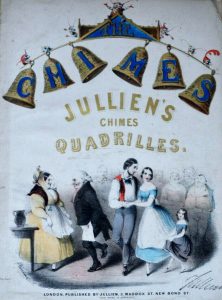

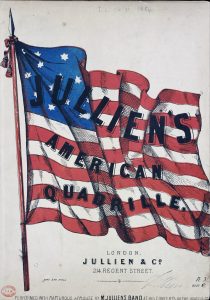

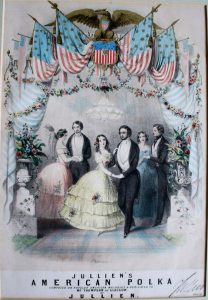

Framed, eye-catching, hand-tinted sheet music covers of a volumninous output of quadrilles, polkas, waltzes and other dances hang on other walls of my home.

Back in 1973, I researched and penned the entry in the then Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians. It’s still there in the current online dictionary (Oxford Music Online).

Jullien published ‘The Celebrated Polka’ many times from 1841 onwards. My own copy is titled ‘The Original Polka’

Jullien was a larger than life character whose declared aim was “to ensure amusement as well as attempting instruction, by blending in the programmes the most sublime works with those of a lighter school.” (Illustrated London News, November 9, 1850).

His audience was the one-shilling public.

Nevertheless, as early as his first London season he gave at least four complete Beethoven symphonies.

The more substantial fare appeared in a musical sandwich, of quadrilles, instrumental solos, galops, waltzes, popular overtures and excerpts from the favourite symphonies.

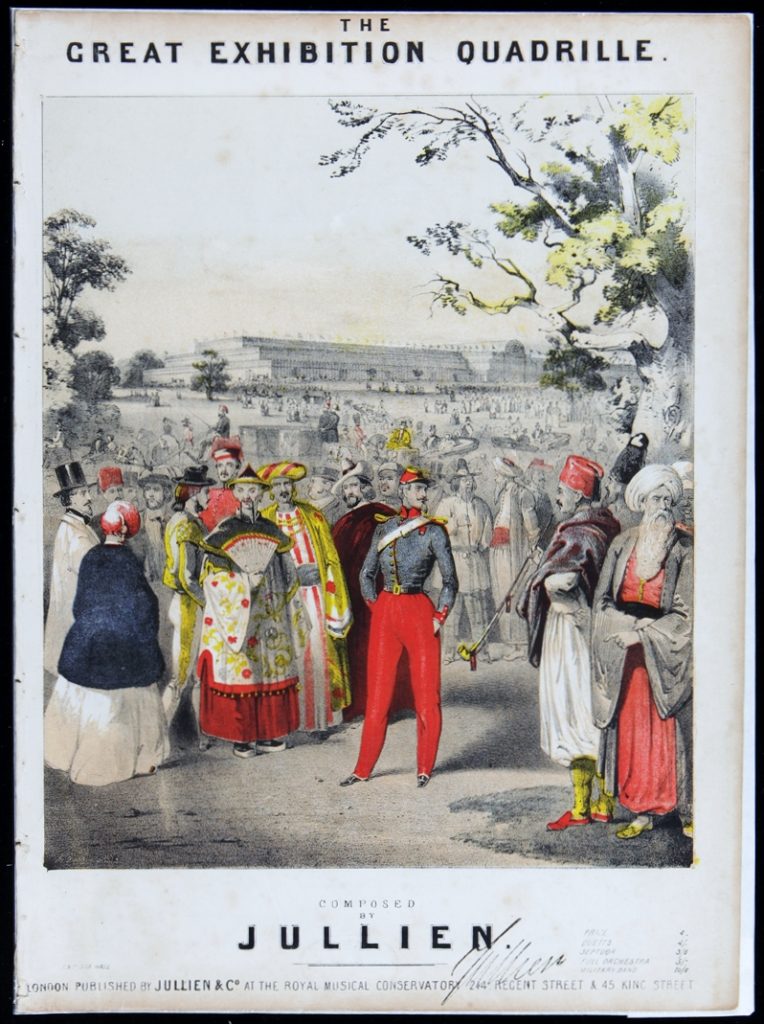

Jullien’s Great Exhibition Quadrille (1851), with the temporary Crystal Palace in London’s Hyde Park on the horizon

Pride of place in a Jullien programme went to the season’s quadrille, often based on a topical theme:

* the Great Exhibition Quadrille (1851)

* the British Navy Quadrille (1845)

* the Swiss Quadrille (1847)

* and – perhaps the most celebrated of all – the British Army Quadrille for orchestra and four military bands (1846).

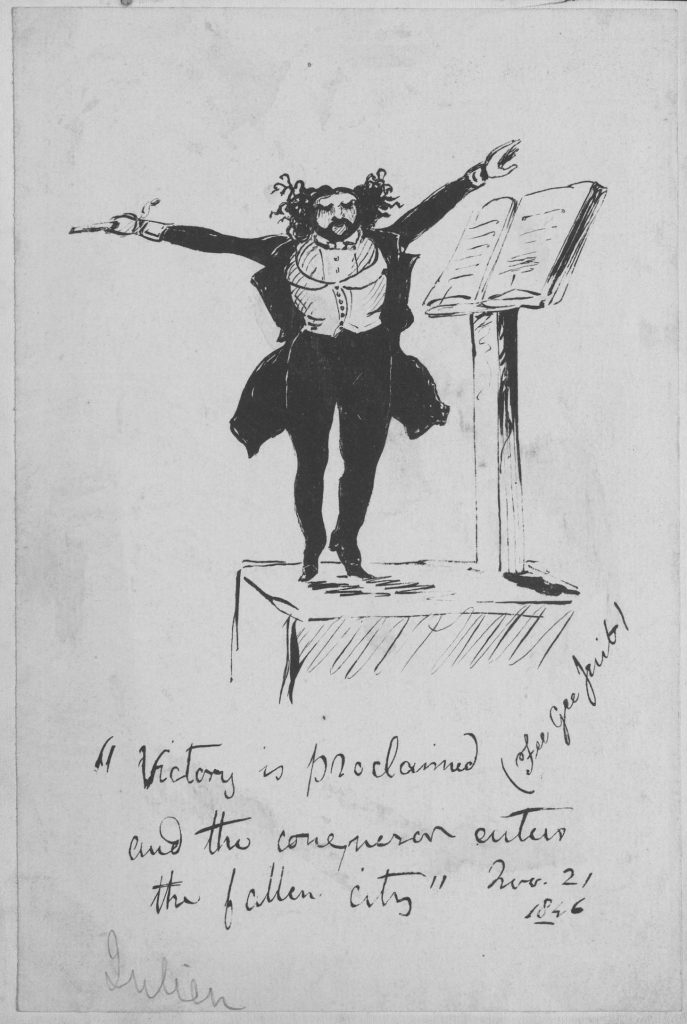

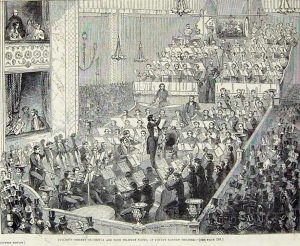

Louis Jullien conducting the ‘British Army Quadrille’ for orchestra and four military bands at Covent Garden Theatre (Illustrated London News, November 7, 1846) CLICK TO ENLARGE

Louis Jullien held a sure command of all the orchestrator’s tricks-of-the-trade, giving a surface charm to what was often second-rate music.

Occasionally it led to excesses, such as the four ophicleides, saxophone and side drums that decorated Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony.

Jullien was born in Sisteron, Basses Alpes, France, April 23, 1812.

His destiny to be considered something of a child prodigy by his violinist-bandmaster father Antonio seemed inevitable after his baptism.

The 36 male members of the Sisteron Philharmonic Society all insisted on becoming godfather to the infant Louis.

So the future conductor was blessed with enough forenames to fill a musical score – and to provide a wealth of pseudonyms when publishing his own music later in life.

Jullien's legal name:

Jullien, Louis George Maurice Adolphe Roch Albert Abel Antonio Alexandre Noé Jean Lucien Daniel Eugène Joseph-le-brun Joseph-Barême Thomas Thomas Thomas-Thomas Pierre Arbon Pierre-Maurel Barthélemi Artus Alphonse Bertrand Dieudonné Emanuel Josué Vincent Luc Michel Jules-de-la-plane Jules-Bazin Julio César

(b Sisteron, France, April 23, 1812; d Paris, March 14, 1860)

Jullien served in the army before entering the Paris Conservatoire around 1833. He left in 1836, preferring dance music over counterpoint and having no diploma or official credit.

For the next three years, Jullien’s lively entertainments of dance music at the Jardin Turc brought rapid popularity, rivalling Musard’s, and three duels brought notoriety.

Insolvent, he speedily left Paris for England in 1838.

Jullien’s first concert there was at the Drury Lane Theatre (June 8, 1840), in a series of ‘concerts d’été.’

Over the following 19 years Jullien’s activities comprised at least 24 promenade concert seasons in the London theatres, four summer seasons, notably of Monster Concerts at the Surrey Zoological Gardens, one and often two provincial tours each year, numerous engagements at balls and private social functions, plus a season of grand opera (1847).

Julllien was no stranger to bankruptcy. But before we get there, I want to focus in on one of his many London concerts, a Monster Concert at the Royal Surrey Zoological Gardens in 1845, when Jullien was in his prime.

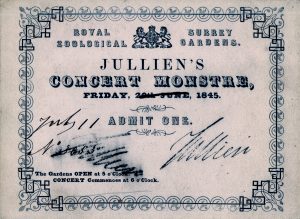

Years ago, I purchased a ticket for the occasion (I was unable to attend, being more than a century too young).

What’s particularly interesting about this ticket is that the original date, Friday June 20, is manually struck out and July 11 inserted in its place. The ticket is also manually numbered and stamped by Jullien.

[Signing tickets and sheet music was his usual practice.

As he puts it on one of my concert playbills –

” . . in order to secure the public against the possibility of purchasing incorrect copies, he has attached his signature to each – none can therefore be relied on which have not his autograph.

Correct copies to be had at all respectable music shops in the Kingdom”].

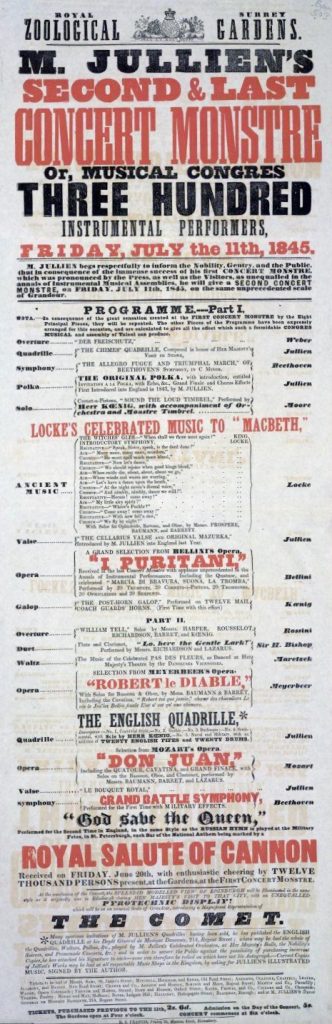

I recently – remarkably – tracked down online a playbill advertising this very concert, July 11, 1845.

“M. JULLIEN begs respectfully to inform the Nobility, Gentry and Public that in consequence of the immense success of his first CONCERT MONSTRE, which was pronounced by the Press as well as the Visitors, as unequalled in the annals of Instrumental Musical Assemblies, he will give a SECOND CONCERT MONSTRE on Friday July 11, 1845, on the same unprecedented scale of Grandeur.”

So, back to my ticket – rather than have a new date set in type, Jullien simply printed additional June 20 tickets and endorsed each of them with a new date, a hand-written ticket number and a stamped signature.

Pre-purchased tickets cost 2s 6d (a half-crown), while tickets at the gate cost 5s.

The music played ranged eclectically from the 17th century English composer Matthew Locke to Weber, Bellini, Meyerbeer, Jullien himself, a selection from Mozart’s Don Giovanni, Beethoven’s ‘Battle’ Symphony ‘with military effects.’

Rounding out the whole occasion, the bill reads –

“‘God save the Queen’, performed for the second time in England, in the same style as the Russian hymn is played at the military fetes, in St. Petersburgh, each bar of the national anthem being marked by a royal salute of cannon received on Friday, June 20th, with enthusiastic cheering by twelve thousand persons present, at the Gardens, at the first concert monstre … pyrotechnic display! … ”

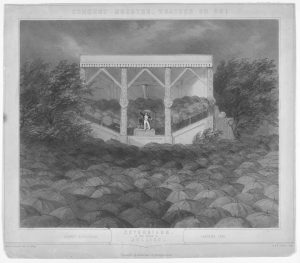

The captions on this now faded, witty cartoon read:

“Concert Monstre. Weather or No!

Surrey Zoological Gardens 1845

Enthusiasm in the reign of Jullien”

Shows Jullien in a yellow waistcoat on the podium, amid a sea of black umbrellas, held by both orchestra and audience, not a face visible!

Jullien had a shrewd eye for publicity and the serio-comic.

He undeniably educated the public during his career, but he was no reformer.

His success was due to his creating new trends and being in the vanguard.

He became a household name and, as a target for the caricaturists, rivalled the leading politicians.

But Jullien’s regular appearances in Punch, where he was referred to as ‘the Mons’, were seldom to his detriment.

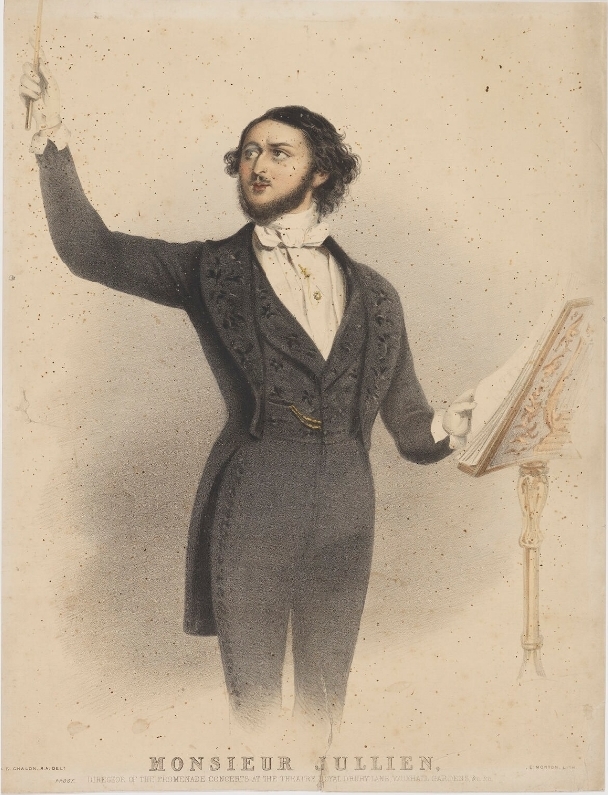

His dress was that of the dandy: raven locks, superb black moustache, coat widely open over gleaming white waistcoat and elegantly embroidered shirt-front.

His red velvet and gilt chair and elaborately decorated music stand were even taken on tour.

He conducted Beethoven with a jewelled baton handed to him on a silver salver.

This cult of the conductor was new.

Behind the pantomime and showmanship lay authority, and Jullien was a pioneer in conducting with the baton. He was able to attract the best of the London players into his orchestras and retained a team of first-class soloists over a number of years.

Berlioz’s grimly amusing account describes him as fundamentally honest but with “the incontestable character of a madman.”

A publishing business started in 1844 had to be sold to pay off debts.

The production – at his own cost – of his reputedly extravagant opera Pietro il grande at Covent Garden in August 1852 was withdrawn after five performances. No one had a good word to say about the work.

“Was that thunder?” a headline read in a review of the opera. “No! It was only Jullien’s opera.”

His personal finances had been in rough shape for years.

It was time to see what America had to offer!

A series of Farewell Concerts throughout the English provinces, Dublin and Scotland was followed by a Testimonial Concert in London.

Services were donated by loyal musicians and singers and the event culminated in the presentation of a jewel encrusted gold and maplewood baton.

It was inscribed: “Presented to M. Jullien by the members of his orchestra, the musical profession of London, and 5,000 of his patrons, admirers and friends, July 11, 1853.”

Jullien took with him principals and core players from his London orchestra, two instrumental soloists (Koenig and Bottesini) and two vocalists.

There were 30 musicians in all – plus 11 TONS of baggage!

New York’s Castle Garden, accomodating 10,000, was the site of the first month’s concerts.

With the orchestra beefed up to 100 with New York’s finest musicians, the public and even the music critics were enthusiastic over Jullien’s mix of classical favourites and virtuoso solo turns, quadrilles, polkas, waltzes and the like.

“Jullien is the strategist of musical art; he deals in vast masses of sound; he collects and gives unity to a hundred different airs, played by as many instruments.”- Wall Street Journal.

“Great is Jullien, and great will be his profits!”- The Spirit of the Times.

“If he plays quadrilles, it is because a man of genius can put his genius into a quadrille as well as into a mass or a symphony, and a good quadrille has more merit than a mediocre mass or symphony.”-New York Tribune.

Three weeks in New York’s Metropolitan Hall brought even more fulsome praise, followed by more concerts along the Eastern seaboard and, early in 1854, even further afield.

In all, Jullien gave 214 concerts in the US, receiving $15,000 per month from the four investors who bankroled the venture.

By way of comparison, his star soloist, double bass virtuoso Giovanni Bottesini, received a handsome $1,000 per month and other soloists proportionately lucrative profits.

After a year away from home, Jullien threw himself into more promenade seasons at the Drury Lane Theatre and Covent Garden, with another tour to Scotland and Ireland. He also gave concerts in Paris, Holland and Belgium, where he had bought a chateau.

In the midst of all this activity there was a disastrous fire at Covent Garden in 1856 in which scores and parts for all Jullien’s major works were destroyed.

Then, the following year, Jullien lost heavily in the collapse of the Surrey Garden Company, now transformed from public pleasure garden with an open-air stage to handsome New Music Hall accomodating 10,000, set amid graceful gardens.

After another round of Farewell Concerts in London and the provinces (1858–9, playing his Hymn of Universal Harmony everywhere), Jullien arrived back in Paris in May 1859.

Plans for a huge ‘Universal Musical Tour’ were abandoned and reports from Berlioz among others described his increasing instability.

As was customary throughout his life, various tales swirl around Jullien’s tragic final weeks.

These are bookended by a documented three months in a Paris debtor’s prison in 1859 and a few days in the Neuilly Maison de Santé, where he died March 14, 1860.

His English-born wife (name unknown), who ran a flower stall at her husband’s promenade concerts, outlived him. She was employed at the box office at the Drury Lane Theatre after his death.

Their only son, Louis, conducted promenade concerts (somewhat unsuccessfully) at Her Majesty’s Theatre in 1863 and 1864.

In the democratization of music and the establishment of the early promenade concert, Jullien’s role was significant.

Natural reserve and reaction against flamboyance by the musical establishment may account for some of the grudging contemporary accounts of his achievement.

English music critic William Davison, however, was a supporter and personal friend: “M. Jullien,” he wrote in an obituary in the Musical World, “was undoubtedly the first who directed the attention of the multitude to the classical composers … [he] broke down the barriers and let in the ‘crowd’.”

Contents © copyright 2021 Keith Horner. Comments welcomed: [email protected]