When Marc-André Hamelin brings his latest delicious, over-the-top, home-baked treat to MusicTORONTO, the confection will be iced with enough piano-insider jokes to give a pianist’s fingers cavities.

Hamelin will venture where few living pianists dare to venture and none can quite bring off with the Montreal-born pianist’s deadpan nonchalance – and chops!

Hamelin’s 10-minute take on Paganini’s fearsome 24th Caprice had a Moscow fan quivering with delight and an audience unable to contain laughter when the Canadian pianist introduced the piece to the Moscow International House of Music one year ago – and to over 40,000 additional fans via that fan’s YouTube video of the performance.

“One of the best days in my life. EVER. I cannot even express how Marc-André’s concert overwhelmed me with ecstatic glee,” s/he wrote in awe of ‘The Omnipotent.’

Hamelin, of course, is playing his way down a path with a rich history, where the performer is also composer. Pianistic bravura first became the stuff of billboard legend in the 1830s, in the wake of the fabulous success of Paganini, the first in a long line of traveling musical virtuosi.

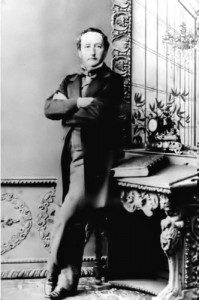

Niccolo Paganini (1782-1840), cadaverous appearance, left foot forward, neck of the violin pointing down, devilish sounds

There was something about the tall, cadaverous Paganini that inspired wild urban legends. Paganini himself went about fanning the flames with glee. He remained aloof from his audience. He deliberately broke strings to demonstrate that four was too many when it came to playing his ferociously difficult music. He wasn’t above using his phenomenal technique to imitate the cries of animals or bagpipes. Paganini, they said, was in league with the devil.

Liszt, emulating Paganini’s transcendental bravura, married charisma with content, bringing wider credibility to the mid-19th century celebration of technical prowess.

Liszt's earliest rival, aristocratic, Swiss-born Sigismond Thalberg (1812-71), whose party trick was dividing a melody between both thumbs amidst cascading arpeggios – giving the illusion of three hands. The trick wore thin and he soon became known as Old Arpeggio

Henri Herz, (1803-88), Austrian-born, whose nimble fingers propelled him to the top layer of salon pianist-composers in Paris in the 1830s and 40s. His vast output of potpourris, variations and other morceaux, his piano factory and round-the-clock teaching made Herz immensely wealthy.

Alexander Dreyschock, (1818-69), Czech pianist with a renowned technique emanating from two right hands, according to one informed, if confused,witness

Hundreds of pianists from across Europe began to vie for attention as Paris became the centre of the piano universe.

Piano wars inevitably resulted.

All these pianists came to the public’s attention at a happy confluence of evolving instrument, evolving public concert and evolving piano technique.

Their operatic fantasies, mostly forgettable, flooded the market. Those by Liszt – and, later, Busoni – set the bar as high as it would go.

When it came to re-creating art from art with the piano transcription, Liszt simply had no equal. In all, he made 145 arrangements of other composers’ music, from Schubert songs and Beethoven symphonies to the stunningly virtuoso masterpiece Réminiscences de Don Juan.

Liszt’s piano transcriptions led to the 19th century becoming the golden age of piano transcription.

Not that the art of transcription itself was new. Its roots stretch back to mediaeval times and to some of the earliest music we know.

Transcription then thrived in the Baroque, with Bach setting the gold standard by which we measure a composer’s success in transforming one medium to another – a violin concerto by Vivaldi, say, into a keyboard concerto by Bach.

Tivadar (Theodor) Szántó (1877-1934). Marc-André Hamelin includes Szántó's grandioso transcription of Bach's Great G minor Fantasia and Fugue

As performer-composers, many of the great composers we are familiar with before Chopin and Liszt were skilled keyboard performers. But none focussed on technique and wrote music to exploit this technique to the same degree as the 19th and early 20th century composer-pianists.

The late Dutch pianist Rian De Waal, who was writing a book on the art of piano transcription before his untimely death in 2011, sees interpretation and transcription as two sides of the same coin.

“In interpretation,” he says, “you try to find out what Beethoven or Schubert could have meant in writing this piece. In making a transcription of the same piece, it is about your own reaction to the piece: your feelings towards it, your fantasy that’s stimulated by it and, very important, the wish to make it available for your instrument.”

The great auto-didact and pianists’-pianist Leopold Godowsky regarded the transcription as a musical essay on a musical subject.

Marc-André Hamelin has recorded Godowsky’s brilliant transcriptions on the Chopin Etudes and Strauss waltzes.

Rachmaninoff, whose music also appears in Hamelin’s MT recital, was one of a generation of pianist-composers whose piano transcriptions delighted audiences on his many concert tours.

The piano transcription as an art form declined in popularity decade by decade throughout the Twentieth century to its present status as an endangered species. Memories of Kempff playing a handful of his elegant Bach transcriptions in the Seventies remain a cherished memory. And even more vivid memories of working with Earl Wild in London on a radio feature about his hair-raising piano transcriptions remain another. Both these very different pianists had roots that stretched deep into the romantic past and both were willing to make their own transcriptions a focal point of their recitals. Today, when not conducting, Russian pianist Mikhail Pletnev helps keep the tradition alive with his Nutcracker and Prokofiev transcriptions. There are others. None more so than Marc-André Hamelin whose January 22 concert will be a date for the memory books.

Marc-André Hamelin (piano)

– Bach/Szántó, Fauré, Ravel, Paganini/Hamelin, Rachmaninoff

Tuesday January 22, 2013 – 8:00 pm. Jane Mallett Theatre,

St. Lawrence Centre for the Arts, 27 Front Street East, Toronto

© copyright Keith Horner 2013