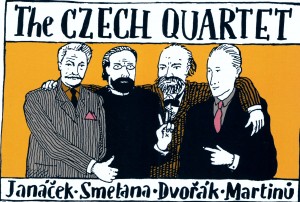

Here’s a curious sidelight on the life of Antonín Dvořák – the viola-playing member of ‘The Czech Quartet’ above. Dvořák’s Op. 61 quartet is featured in the Apollon Musagète Quartet concert this November

Here’s a curious sidelight on the life of Antonín Dvořák – the viola-playing member of ‘The Czech Quartet’ above. Dvořák’s Op. 61 quartet is featured in the Apollon Musagète Quartet concert this November

A small exhibition at the Dvořák Museum in Prague highlights the fascination that the Bohemian composer had with the steam locomotive.

This is how Dvořák spoke of trains in a conversation recalled by his student Josef Michl, after the two of them saw a train near the small country property the composer owned in Vysoká, just South of Prague:

“I [Dvořák] especially like the huge and clear ingenuity with which the locomotive is constructed! It consists of many parts created by many different components.

Each of them has its importance; each of them is right in place.

Even the smallest screw is in the correct place, being used to hold something.

Everything has a purpose and role and the result is amazing. Such a locomotive can be put on the track and filled with water and coal. One person moves with a small lever and the big levers start to move too. Even though the carriages weigh a few thousand quintals, the locomotive runs as quickly as a rabbit with them!”

Dvořák was nine and living in Nelahozeves when he witnessed his first train, carrying miltary personnel, in the spring of 1850. It was on a branch of the main line from Prague to Dresden, passing through Nelahozeves and Kralupy to Podmokly.

Nelahozeves was a farming outpost, lying on the Vltava River, within the large estates owned by the Lobkowitz (Lobkowicz) family – a name familiar to music-lovers via Prince Joseph Lobkowitz, one of Beethoven’s key patrons.

Today, Dvořák’s house, Building No. 12 in this then rural community of a little over 400 permanent residents, remains, as it was during Dvořák’s childhood, directly across from the station.

His father, František, rented rooms in the property and ran the inn on the main floor – though his interest in running the business (and that of his earlier occupation as butcher at Building No. 24) increasingly came second to that of playing the zither.

Once freight started being carried on the line in 1851, Dvořák’s curiosity in the latest form of transportation was piqued.

In his maturity, when traveling in Europe or the United States, Dvořák would avidly – some would say obsessively – comb railway timetables to plan his best connections.

He would also keep records, such as details on the express trains traveling from Prague to Vienna.

His habitual early morning walk when living in Prague would take him above the tunnel, just beyond the historic Vinohrady quarter of Prague, through which trains would exit from Prague’s splendidly grand main station.

Dvořák was reported to regularly chat with train drivers to find out about the latest technical innovations on the trains.

He was also a trainspotter, collecting the engine numbers of the express trains from Prague to Vienna and Dresden.

Dvořák once asked one of his students at the Prague Conservatoire, composer Josef Suk, to wake up early and record the engine number of the Vienna express train as it came out of the tunnel.

The young Suk obliged – as befits a future son-in-law – taking his opera glasses to ensure accuracy.

No train-spotter he, Suk duly reported back to Dvorak’s apartment in Žitná street with a train number . . . not of the engine itself, but of the tender at the back of the train.

A workman here installs marble on a balcony at Žitná Street No. 564, alongside a new bust of the building’s most famous resident: ‘Dr. Antonín Dvořák – composer.’

The five-storey apartment block at Žitná Street No. 564 is currently under renovation.

Dvořák lived here, in four different apartments as the size of his family changed, from 1877 to his death in 1904.

The impact of Dvořák’s train-spotting hobby on his music is . . . well . . . mostly intangible. But there are shared qualities between what Dvořák saw as the precision and elegance of a steam locomotive’s design, construction, and function with one of his own carefully crafted scores. At its best (and there are a surprising number of gems in his catalogue), a Dvořák score is designed to sound natural, uncomplicated, spontaneous and ‘right’ on its chosen instrument – these are honest, hard-working qualities achieved through both inspiration and perspiration.

It’s quite often said that the famous Humoresque (No. 7 from his last piano collection, Op. 101)CLICK is inspired by the movement of a train. I don’t hear it, myself.

On the other hand, No. 6 from the same collection CLICK certainly opens with the sound of a North American train whistle and continues with an accelerating motion not unlike that of a train. The Op. 101 collection uses sketches that Dvořák made in notebooks during his three years in the United States. So, just maybe . . .

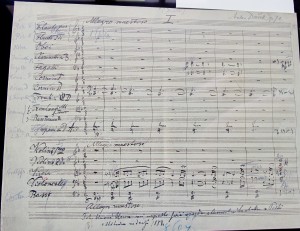

There is a solid connection between Dvořák and trains in the Seventh Symphony, however. Here’s the manuscript score of the opening movementCLICK.

At the very bottom, Dvořák’s handwritten note reads:

“I got this theme when the festival train from Pest was arriving in the State Station in 1884.”

The train was bringing several hundred anti-Habsburg sympathisers from Budapest to Prague for a festival at the National Theatre. Nationalists – and Dvořák strongly identified himself with the rising tide of Bohemian nationalism – had been tracking the group’s progress through Moravia and Bohemia with enthusiasm. Dvořák was at the station with them when the ominous, stirring theme, rich in ideas for development, came to him.

Dvořák was artistic director and professor of composition of the American National Conservatory of Music and based in New York for almost three years, 1892-5.

Dvořák was artistic director and professor of composition of the American National Conservatory of Music and based in New York for almost three years, 1892-5.

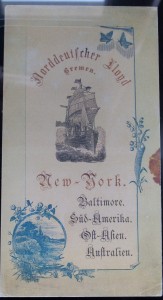

To the right is the boarding pass that got him on board the S.S. Saale which took him to the United States.

But when it came to watching the trains at Grand Central Station, the famous composer had no such privileges. Only ticket-holders were allowed on the platforms. From his East 17th Street apartment, it was too time-consuming to travel to a good vantage point where he could spot the inter-city New York to Boston or Chicago trains. So what to do?

Well, there were always the pigeons (sic)!

Dvořák often went to see them – pigeons, that is – in the gardens in Central Park. Back home, he specialised in breeding pouter and fantail pigeons among the many he kept in a pigeon loft at Vysoka. He had even been sent a gift from one member of the British royal family after they had found out that the Bohemian composer had a thing for pigeons – two braces of English pouters and four braces of wig pigeons, no less.

The excitement on Dvořák’s face is palpable as he presides over his loft (or kit) of pigeons at Vysoka

Pigeons, however, were but a sideline for Dvořák’s main New York hobby: trans-Atlantic ocean liners. Here was a hobby with both technology and a timetable (of sorts), just like his beloved trains. The arrivals and departures from the New York port were to be found in the New York Herald. Dvořák mapped them out and, as his biographer John Clapham narrates, toured every ship bound for Europe from bow to stern, making friends with their captains.

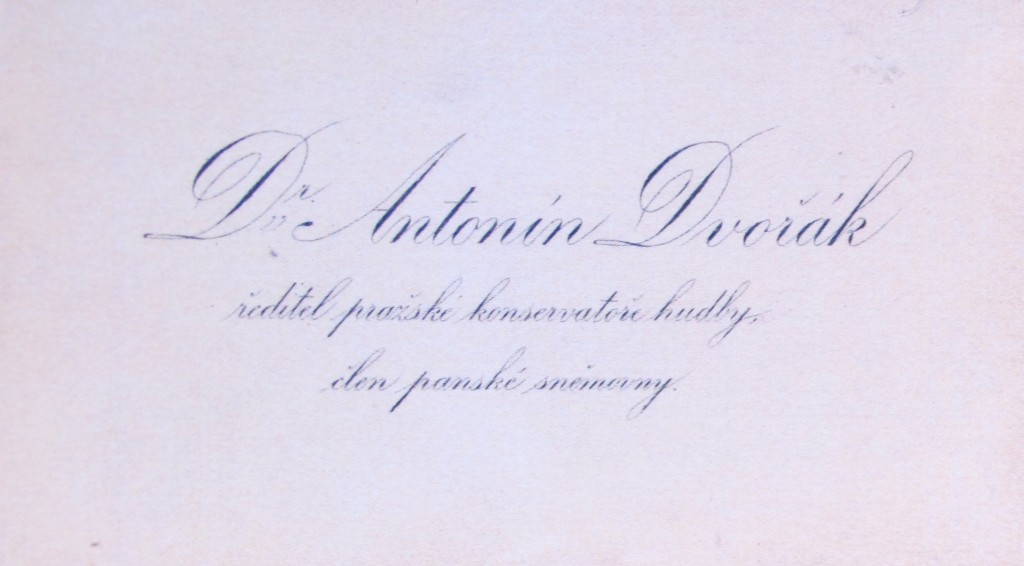

Business card of Dr. Antonín Dvořák Director of the Prague Conservatory of Music Member of Parliament

But, once Mrs. Thurber’s noble plans for her New York Conservatory crumbled and Dvořák returned to the country of his birth, train-spotting again resumed its place in the composer’s priorities.

He was appointed as a member of the Herrenhaus of the Austrian government in March 1901 (a sort of MP – though he attended just one session of the parliament).

Then came the Directorship of the Prague Conservatory later that same summer (with an assistant doing all the admin).

Still, Dvořák found time for his trains. They were to remain important to him right to the end.

He was now well into his sixties. Even days after a severe pain in his side gave cause for concern during production rehearsals for his last opera Armida, Dvořák insisted on walking to the Franz Joseph I central station to view the locomotives and chat with an engineer. He caught a chill and never recovered. A few days later, on May 1, 1904, Antonín Dvořák, composer, train-spotter, pigeon-fancier died.

Dvořák’s C major quartet, Op. 61 opens the Toronto début concert of the Apollon Musagète Quartet, November 26, 2015.

Antonín Dvořák Museum, Ke Karlovu 20, Prague.

© copyright 2015 Keith Horner – [email protected]