In his season-opening concert – his 12th on the MusicTORONTO stage – Canadian virtuoso Marc-André Hamelin includes some of his favourite piano transcriptions. They include six by Mr Nobody.

Piano transcriptions, you say?

Not the real thing?

Secondhand piano music?

Mr Nobody? A composer who daren’t show his face?

Let’s start where Marc-André will start his recital, with what is probably the most transcribed of all pieces in the classical repertoire: the Chaconne which closes Bach’s D minor Partita for solo violin in grand style.

Mendelssohn was the earliest to make the modest sound of Bach’s violin more ‘alive’ for an early 19th c concert audience by filling out the harmonies of the solo line by adding piano accompaniment. (Violinist Catherine Manoukian played Mendelssohn’s version, together with Schumann’s paler attempt to spice up the Chaconne for MusicTORONTO back in 2002. Anyone remember?).

Later on, we find Brahms writing to Clara Schumann and saying that by putting his left-hand to work and giving his right-hand the night off, playing his own left-hand transcription “makes me feel like a violinist.”

But Brahms was too respectful to Bach’s score and it took the one-armed Swiss pianist Paul Wittgenstein (1887-1961) to put the pianistic fireworks into a left-hand transcription for piano – in the process, extending Bach’s three-octave range and Brahms’s four, to 5.5 octaves.

Little space to mention impressive efforts made with Chaconne transcriptions for other instruments here. Lingering for a moment over a reverential, almost religious performance of his Busoni-inspired transcription for guitar that I heard from a silver-haired Segovia in Oxford’s Sheldonian Theatre back in the early 1970s.

And there was the ghostly, often ethereal, but still rich dumpling of an orchestral transcription that the 92-year-old Leopold Stokowski recorded with the LSO for Decca in St Giles church, Cripplegate in that same long-gone era.

Ferruccio Dante Michelangelo Benvenuto Busoni, on the other hand, took another approach, as you might expect with a composer whose very name reads like a transcription.

First, he re-imagined the Chaconne transcribed for organ in his mind, then he set to work transcribing this mental sonic picture for the piano.

Busoni uses all the piano registers, just about the full 7.25 octaves of the keyboard, from the lowest A to highest B-flat, and all three pedals.

The resulting masterpiece, bristling with four or five layers of counterpoint and eight or nine-voiced chords, will come alive under the fingers of Marc-André Hamelin.

Maybe you’ll be persuaded to join me in believing that a great composer-pianist can be inspired to create a transcription which not only casts new light on the original, but stands in its own right as an artistic creation of equal grandeur.

Chaconne à son goût! . . . “Chacun sa chaconne!”**

Which brings us to Mr Nobody and his brilliant efforts to bring French popular café songs to the concert platform. Just listen to this shimmering transcription of En Avril, à Paris by Mr Nobody.

Mr Nobody’s En Avril, à Paris is like an intricately-woven spider’s web, glistening in the sun, wrapped around a simple six-note earworm of a tune.

Here’s another transcription, this time a glittering, less-than-one-minute take by Mr Nobody on Trenet’s 1938 story of lost love left behind in the hilly quarter of Paris known as Ménilmontant.

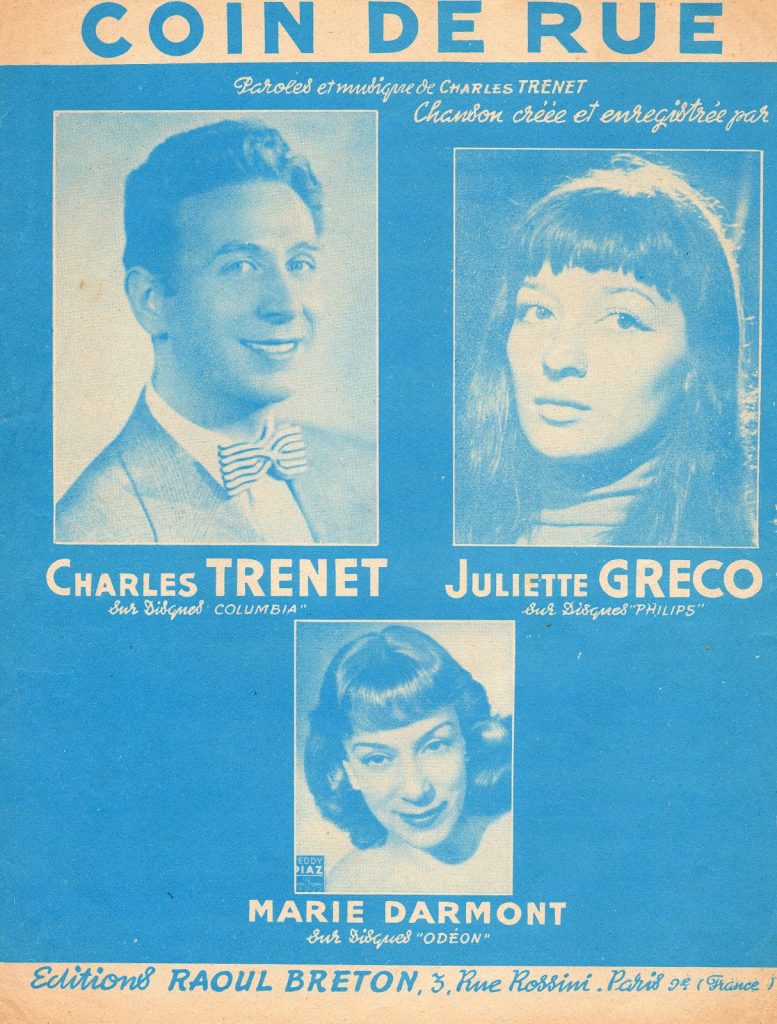

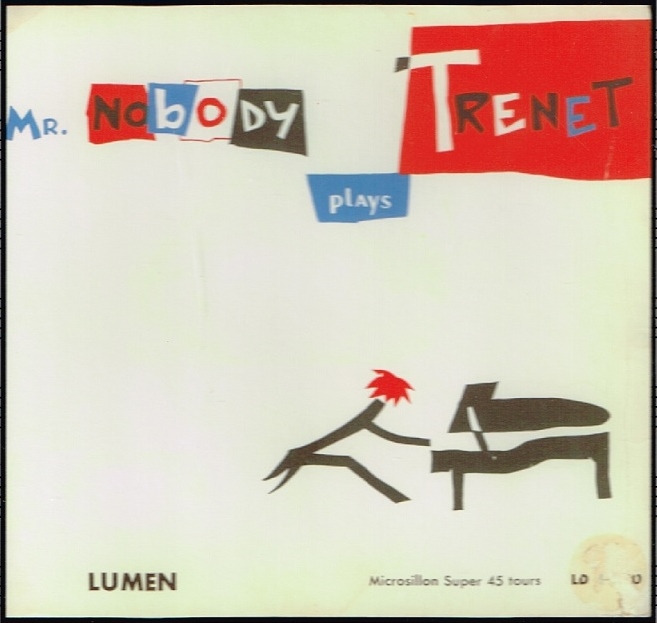

Mr Nobody released six of his arrangements of songs sung by Charles Trenet (1913–2001), the most influential popular French singer-songwriter of the mid-20th century, in the 1950s on a 45-rpm EP record on the Lumen label.

Cassette copies circulated. Insiders, of course, knew or had a good idea of the identity of the clearly brilliant pianist behind the release. (Marc-André Hamelin tells the tale in the MusicTORONTO program notes). But only in relatively recent times has it become publicly known that the pianist was Alexis Weissenberg (1929-2012).

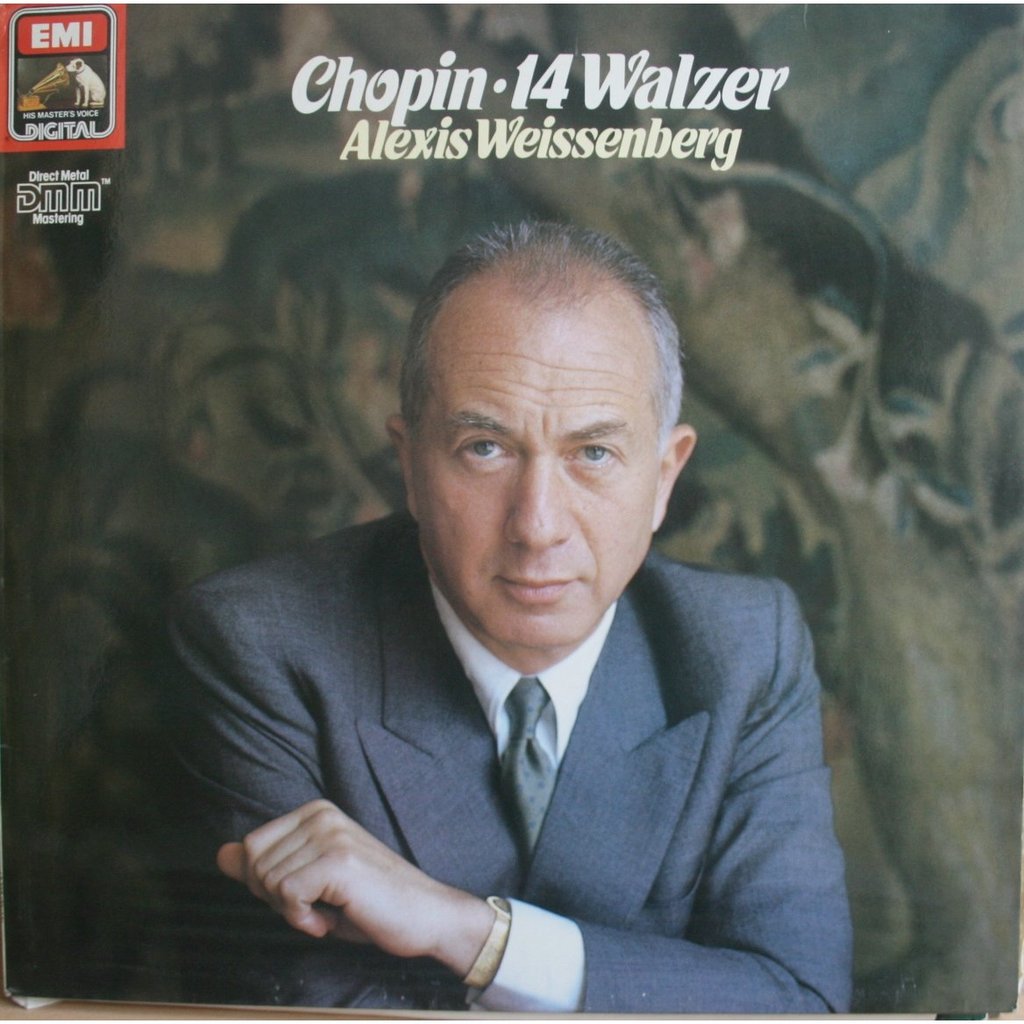

The career of the Bulgarian-born, longtime Paris resident had its ups (winner of the 1947 prestigious Leventritt Award, then international bookings) and its downs (a decade under the radar, unhappy with his interpretations and career, working on his technique, teaching). Then more ups (recording all five Beethoven Concertos with Karajan and the Berlin Phil for EMI, decades at the top of his game performing and recording most of the standard rep) – and downs (he disappeared once more, eventually dying in Madrid from Parkinson’s disease).

Weissenberg was famously criticised for the cold precision of a finely-honed, prodigious technique, offering, in the words of one critic, “all the warmth and humanity of an autopsy.” When asked how much of his playing was intuitive and how much pre-planned,Weissenberg bit back at his interviewer: “All of it is intuitive and all of it is pre-planned.”

The name “Mr Nobody” was dreamed up to prevent negative association with crossover music long before the term was invented. Anonymity gave Weissenberg permission to explore a less buttoned, side of his complex, highly cultured, eloquently-spoken personality. This was the side that French tv viewers saw in the 1970s and 80s when the good-looking, sharply-dressed, suavely-spoken pianist could be seen as accompanist to the likes of Charles Aznavour and Nana Mouskouri.

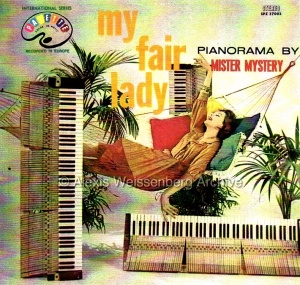

“Mister Mystery” was another nom de plume of the pianist, who took French citizenship.

Weissenberg’s sleeve notes for the original 45-rpm release of his own transcriptions of melodies from My Fair Lady give an entertaining description of how to go about the serious business of making a piano transcription — the process of successfully transfering one musical medium to another.

|

“You take a tune you like and play it inside out, for yourself, until you are sick of it,” Weissenberg says. “Then, the first thing you have to do about it is forget it. Forget it, honestly; play other things, other tunes. “When you come back to it, the tune will have ripened, ‘matured’, in your head, in your heart, in your feet, wherever you like. Don’t touch the score again. Play it the way you think you remember it. Your way. “Now you have the basic element of your concoction. Put it in the shaker such as it is, or upside down, if you prefer. At this point, before adding ice cubes or egg yolks, (which in musical terms are called harmonies and modulations), you have to think up carefully the ‘spices’ you want to mix to make it really a ‘Special’, ‘Tops’, or an A-Plus’ beverage. “Think hard. Olives, mustard, pepper, Angostura, mint, sugar, lemon, lime, Worcestershire, and Ketchup correspond, in music, to rhythms, trills, sound-effects, counterpoints, syncopated notes, triplets, glissandi, and such happy combinations as a schizophrenic battery and a non-committal bass, and, from time to time, the use of a triangle, of course. “Once the choice is established, add the spices to your basic element. If necessary, multiply them. Put in an extra melody, if you so desire. Close the shaker tight and shake. Shake hard. When you open the shaker and pour out the content, you’ll have an arrangement all your own.” |

Somebody should have told Busoni it is that easy!

Jazz colours many of Weissenberg’s compositions, which include a musical, Nostalgie, which premièred in 1992 and a musical comedy La fugue, which Martha Argerich presented in Lugano in 2008 (well into Weissenberg’s illness). Marc-André Hamelin brought Weissenberg’s 1982 Sonata in a State of Jazz to MusicTORONTO a few years ago. It’s a kind of jazz re-mix in which he distils the essence of four types of jazz popular in the 1950s – the tango, charleston, blues and samba – and structures them within a classical framework.

Earlier times are recalled with these selections from the Charles Trenet collection which Marc-André Hamelin will be playing in his 2018-19 season opener next month – and which you can hear Mr Nobody play right now!

Visit this growing archive for more rare recordings, interviews, photos, videos and much more. http://alexisweissenbergarchive.com/

** FOOTNOTE: “Chacun sa chaconne” are the concluding words of a chapter on Bach transcriptions from a book on virtuoso piano transcriptions by a brilliant pianist and dear colleague, Rian de Waal (1958-2011) with whom I worked on several projects. Metamorphoses: the art of the virtuoso piano transcription is published by Eburon Publishers, Delft (2013) and includes 6 CDs containing 50 tracks of professionally recorded virtuoso transcriptions, many of which are rarieties.

Marc-André Hamelin plays Bach-Busoni, Feinberg, Weissenberg-Trenet, Castelnuovo-Tedesco and Chopin, Tuesday October 2, 2018

© copyright 2018 Keith Horner – [email protected]